Enumeration & Brute Force

Enumerating Users via Verbose Errors

Understanding Verbose Errors

Imagine you're a detective with a knack for spotting clues that others might overlook. In the world of web development, verbose errors are like unintentional whispers of a system, revealing secrets meant to be kept hidden. These detailed error messages are invaluable during the debugging process, helping developers understand exactly what went wrong. However, just like an overheard conversation might reveal too much, these verbose errors can unintentionally expose sensitive data to those who know how to listen.

Verbose errors can turn into a goldmine of information, providing insights such as:

Internal Paths: Like a map leading to hidden treasure, these reveal the file paths and directory structures of the application server which might contain configuration files or secret keys that aren't visible to a normal user.

Database Details: Offering a sneak peek into the database, these errors might spill secrets like table names and column details.

User Information: Sometimes, these errors can even hint at usernames or other personal data, providing clues that are crucial for further investigation.

Inducing Verbose Errors

Attackers induce verbose errors as a way to force the application to reveal its secrets. Below are some common techniques used to provoke these errors:

Invalid Login Attempts: This is like knocking on every door to see which one will open. By intentionally entering incorrect usernames or passwords, attackers can trigger error messages that help distinguish between valid and invalid usernames. For example, entering a username that doesn’t exist might trigger a different error message than entering one that does, revealing which usernames are active.

SQL Injection: This technique involves slipping malicious SQL commands into entry fields, hoping the system will stumble and reveal information about its database structure. For example, placing a single quote (

') in a login field might cause the database to throw an error, inadvertently exposing details about its schema.File Inclusion/Path Traversal: By manipulating file paths, attackers can attempt to access restricted files, coaxing the system into errors that reveal internal paths. For example, using directory traversal sequences like

../../could lead to errors that disclose restricted file paths.Form Manipulation: Tweaking form fields or parameters can trick the application into displaying errors that disclose backend logic or sensitive user information. For example, altering hidden form fields to trigger validation errors might reveal insights into the expected data format or structure.

Application Fuzzing: Sending unexpected inputs to various parts of the application to see how it reacts can help identify weak points. For example, tools like Burp Suite Intruder are used to automate the process, bombarding the application with varied payloads to see which ones provoke informative errors.

The Role of Enumeration and Brute Forcing

When it comes to breaching authentication, enumeration and brute forcing often go hand in hand:

User Enumeration: Discovering valid usernames sets the stage, reducing the guesswork in subsequent brute-force attacks.

Exploiting Verbose Errors: The insights gained from these errors can illuminate aspects like password policies and account lockout mechanisms, paving the way for more effective brute-force strategies.

In summary, verbose errors are like breadcrumbs leading attackers deeper into the system, providing them with the insights needed to tailor their strategies and potentially compromise security in ways that could go undetected until it’s too late.

Enumeration in Authentication Forms

In this HackerOne report, the attacker was able to enumerate users using the website's Forget Password function. Similarly, we can also enumerate emails in login forms. For example, navigate to http://enum.thm/labs/verbose_login/ and put any email address in the Email input field.

When you input an invalid email, the website will respond with "Email does not exist." indicating that the email has not been registered yet.

However, if the email is already registered, the website will respond with an "Invalid password" error message, indicating that the email exists in the database but the password is incorrect.

Automation

Below is a Python script that will check for valid emails in the target web app. Save the code below as script.py.

We can use a common list of emails from this repository.

Once you've downloaded the payload list, use the script on the AttackBox or your own machine to check for valid email addresses.

Kali

Exploiting Vulnerable Password Reset Logic

Password Reset Flow Vulnerabilities

Password reset mechanism is an important part of user convenience in modern web applications. However, their implementation requires careful security considerations because poorly secured password reset processes can be easily exploited.

Email-Based Reset

When a user resets their password, the application sends an email containing a reset link or a token to the user’s registered email address. The user then clicks on this link, which directs them to a page where they can enter a new password and confirm it, or a system will automatically generate a new password for the user. This method relies heavily on the security of the user's email account and the secrecy of the link or token sent.

Security Question-Based Reset

This involves the user answering a series of pre-configured security questions they had set up when creating their account. If the answers are correct, the system allows the user to proceed with resetting their password. While this method adds a layer of security by requiring information only the user should know, it can be compromised if an attacker gains access to personally identifiable information (PII), which can sometimes be easily found or guessed.

SMS-Based Reset

This functions similarly to email-based reset but uses SMS to deliver a reset code or link directly to the user’s mobile phone. Once the user receives the code, they can enter it on the provided webpage to access the password reset functionality. This method assumes that access to the user's phone is secure, but it can be vulnerable to SIM swapping attacks or intercepts.

Each of these methods has its vulnerabilities:

Predictable Tokens: If the reset tokens used in links or SMS messages are predictable or follow a sequential pattern, attackers might guess or brute-force their way to generate valid reset URLs.

Token Expiration Issues: Tokens that remain valid for too long or do not expire immediately after use provide a window of opportunity for attackers. It’s crucial that tokens expire swiftly to limit this window.

Insufficient Validation: The mechanisms for verifying a user’s identity, like security questions or email-based authentication, might be weak and susceptible to exploitation if the questions are too common or the email account is compromised.

Information Disclosure: Any error message that specifies whether an email address or username is registered can inadvertently help attackers in their enumeration efforts, confirming the existence of accounts.

Insecure Transport: The transmission of reset links or tokens over non-HTTPS connections can expose these critical elements to interception by network eavesdroppers.

Exploiting Predictable Tokens

Tokens that are simple, predictable, or have long expiration times can be particularly vulnerable to interception or brute force. For example, the below code is used by the vulnerable application hosted in the Predictable Tokens lab:

The code above sets a random three-digit PIN as the reset token of the submitted email. Since this token doesn't employ mixed characters, it can be easily brute-forced.

To demonstrate this, go to http://enum.thm/labs/predictable_tokens/.

Navigate to the application's password reset page, input "admin@admin.com" in the Email input field, and click Submit.

The application will respond with a success message.

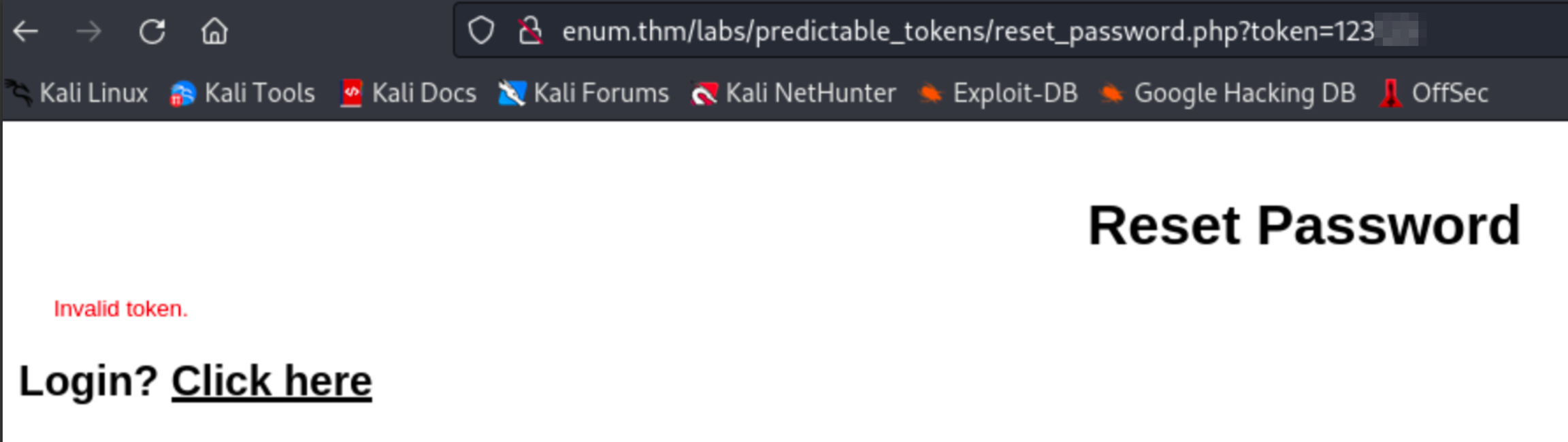

For demonstration purposes, the web application uses the reset link: http://enum.thm/labs/predictable_tokens/reset_password.php?token=123

Notice the token is a simple numeric value. Using Burp Suite, navigate to the above URL and capture the request.

Subsequently, send the request to the Intruder, highlight the value of the token parameter, and click the Add payload button, as shown below.

Using the AttackBox or your own attacking VM, use Crunch to generate a list of numbers from 100 to 200. This list will be used as the dictionary in the brute-force attack.

Kali

Go back to Intruder and configure the payload to use the generated file.

The attack will take some time to finish if you're using Burp Suite Community Edition. However, once successful, you will get a response with a much bigger content length compared to the responses with an "Invalid token" error message.

Log in to the application using the new password.

Exploiting HTTP Basic Authentication

Basic Authentication in 2k24?

Basic authentication offers a more straightforward method when securing access to devices. It requires only a username and password, making it easy to implement and manage on devices with limited processing capabilities. Network devices such as routers typically utilise basic authentication to control access to their administrative interfaces. In this scenario, the primary goal is to prevent unauthorized access with minimal setup.

While basic authentication does not offer the robust security features provided by more complex schemes like OAuth or token-based authentication, its simplicity makes it suitable for environments where session management and user tracking are not required or are managed differently. For example, in devices like routers that are primarily accessed for configuration changes rather than regular use, the overhead of maintaining session states is unnecessary and could complicate device performance.

HTTP Basic Authentication is defined in RFC 7617, which specifies that the credentials (username and password) should be transported as a base64-encoded string within the HTTP Authorization header. This method is straightforward but not secure over non-HTTPS connections, as base64 is not an encryption method and can be easily decoded. The real threat often comes from weak credentials that can be brute-forced.

HTTP Basic Authentication provides a simple challenge-response mechanism for requesting user credentials.

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Authentication

The Authorization header format is as follows:

where <credentials> is the base64 encoding of username:password. For detailed specifications, refer to RFC 7617.

Exploitation

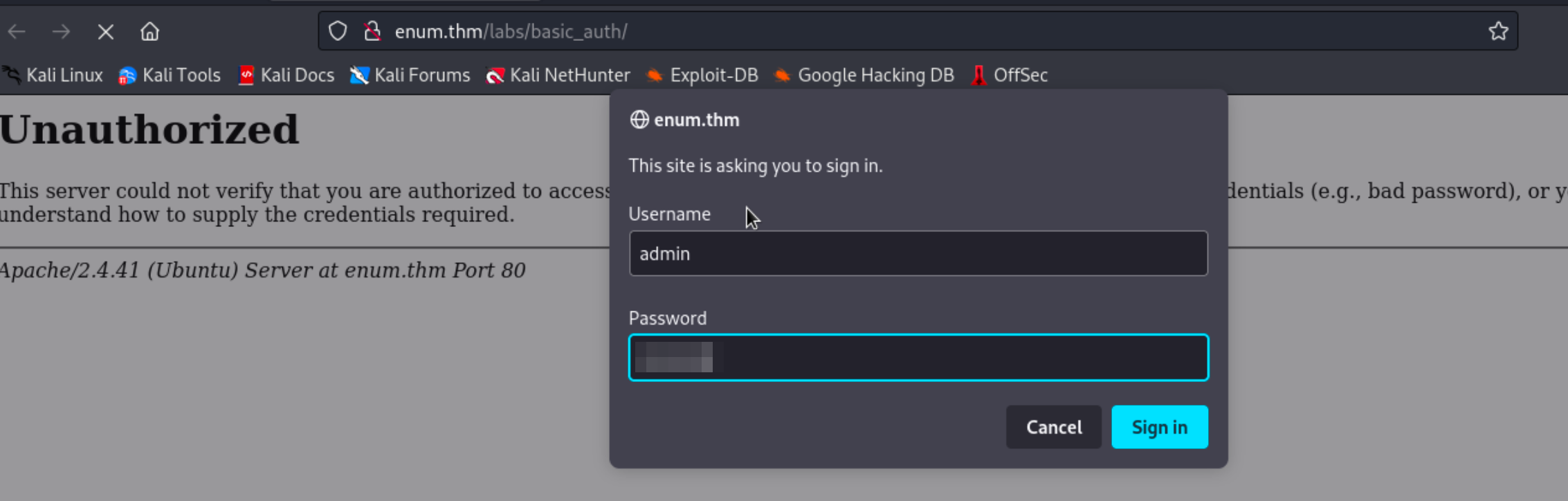

To demonstrate this, go to http://enum.thm/labs/basic_auth/.

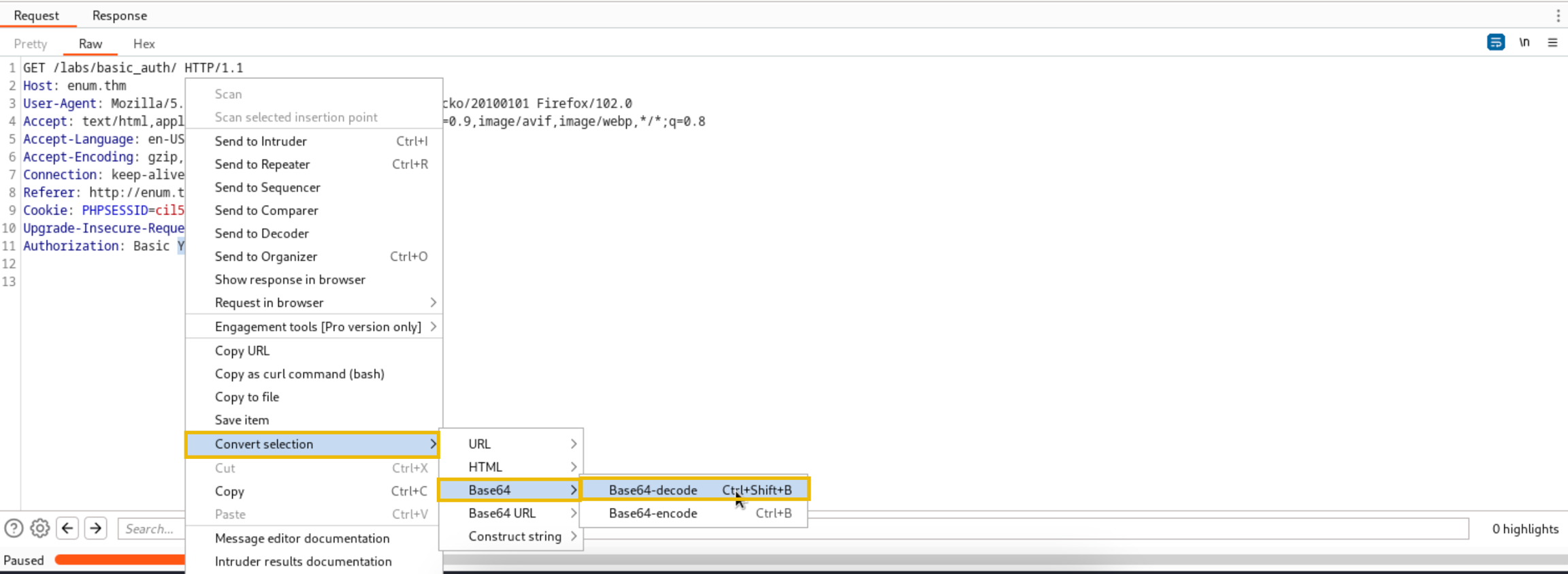

Input any username and password in the pop-up and capture the Basic Auth Request using Burp.

Right-click the request and send it to Intruder.

In Burp Intruder, go to the "Positions" tab and decode the base64 encoded string in the Authorization header.

Once decoded, highlight the decoded string and click the Add button in the top right corner.

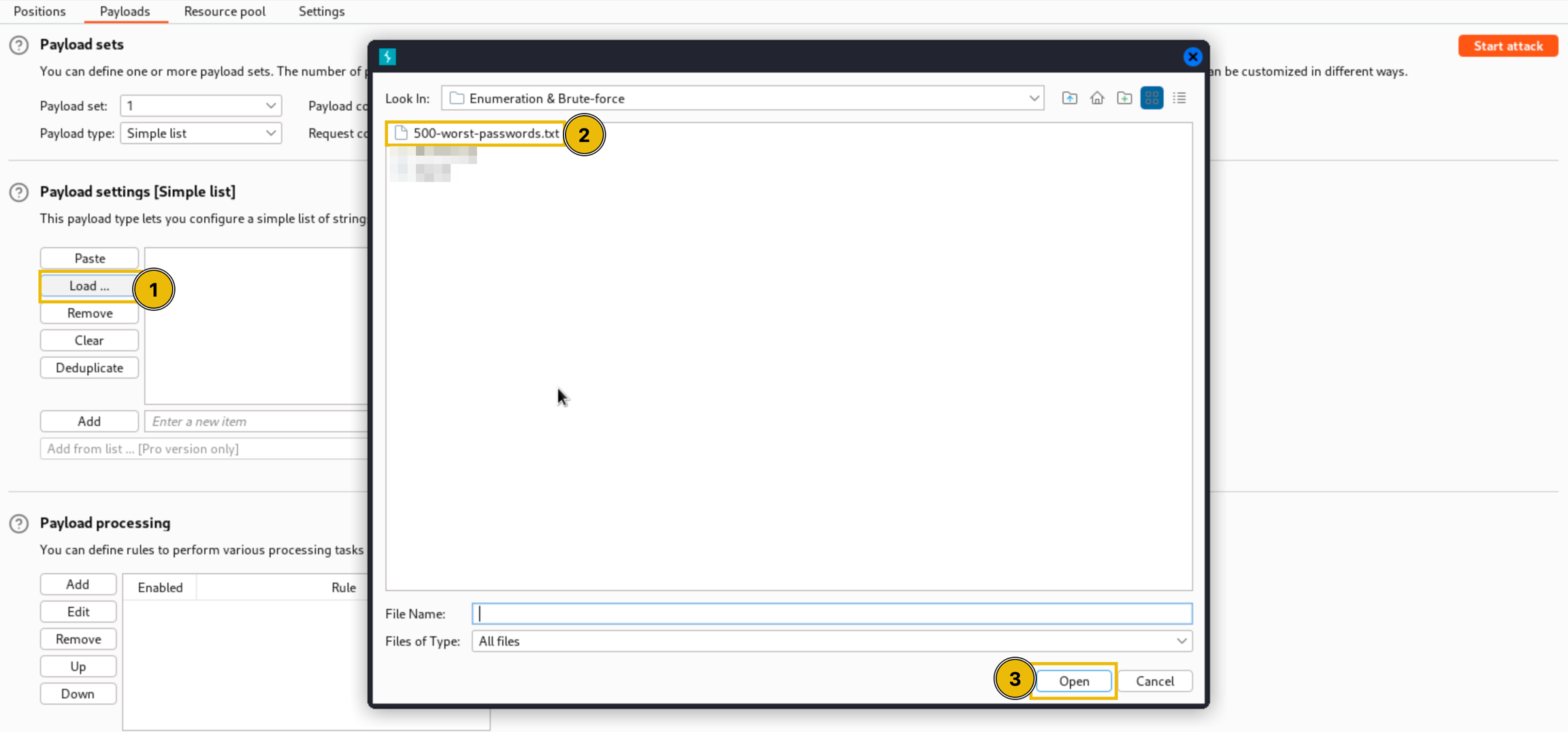

Next is configuring the payloads. Go to the Payloads tab and set the payload type to Simple list and choose your preferred wordlist. In this demo, we will use the 500-worst-passwords.txt from SecLists. If you're using the AttackBox, you may use the same wordlist located at /usr/share/wordlists/SecLists/Passwords/Common-Credentials/500-worst-passwords.txt.

Since the header is base64 encoded, we need to add two rules in the Payload processing section. The first automatically adds a username to the password, so instead of 123456, the payload will be "admin:123456".

The second rule will base64 encode the combined username and password from the supplied list.

We should also remove the character "=" (equal sign) from the encoding because base64 uses "=" for padding. To do this, scroll down and remove the "=" sign from the list of characters in the Payload encoding section.

Once done, go back to the Positions tab and click the Start Attack button. The attack will take a little less than 2 minutes.

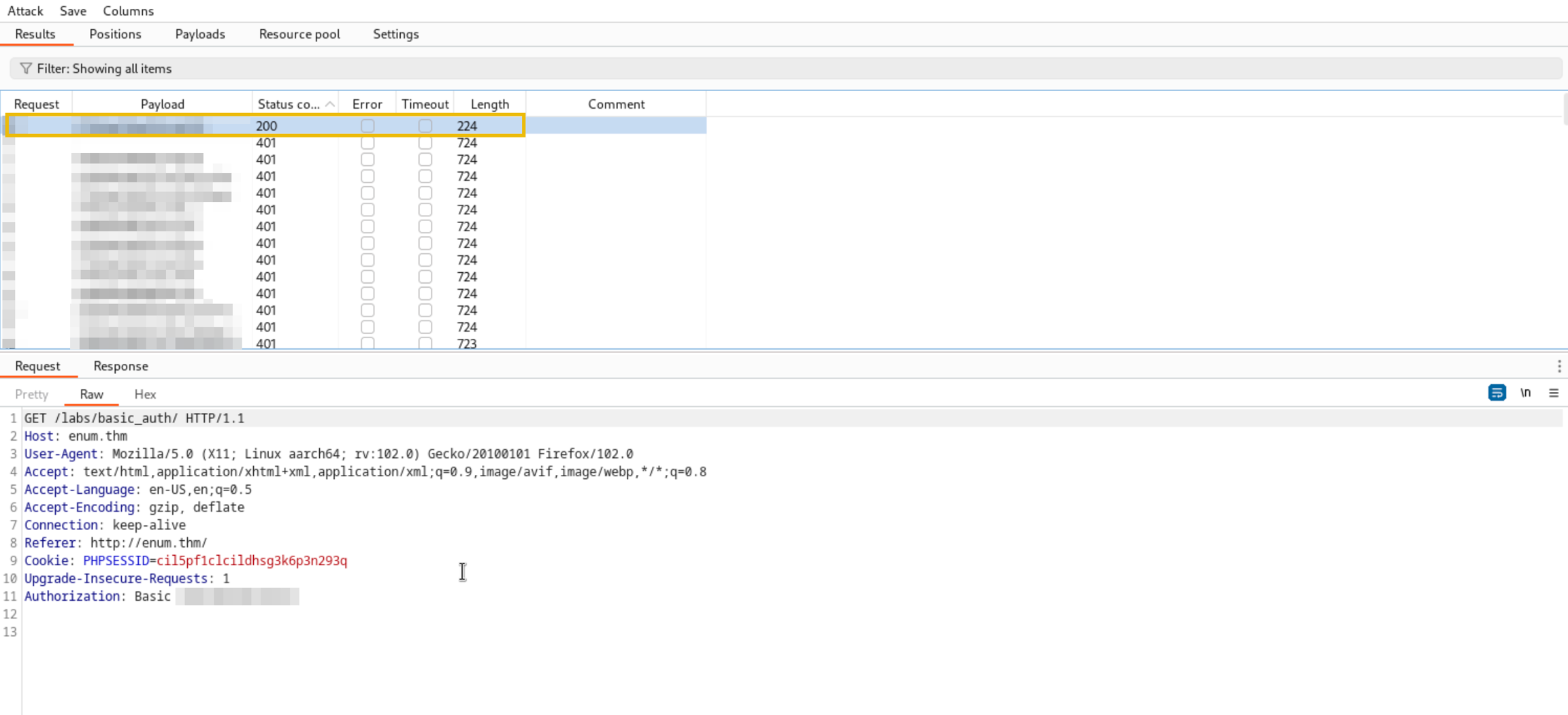

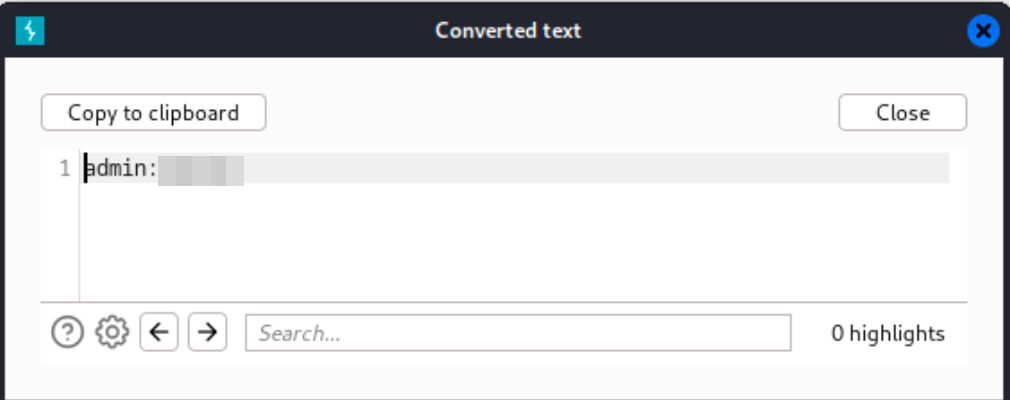

Once you get a Status code 200, it means the brute force is successful, and one of the passwords in the supplied list is working. Decode the encoded base64 string in the successful request.

Use the decoded base64 string to log into the application.

Hydra

Kali

Last updated