DOM-Based Attacks

Room Link: https://tryhackme.com/r/room/dombasedattacks

The DOM Explained

Before we can dive into DOM-based attacks, we need to explain what the DOM is first. DOM refers to the Document Object Model, which is the programming interface that displays the web document. When you make a request to a web application, the HTML in the response is loaded as the DOM in the browser. In essence, the DOM is the programmatic view of the web application that the user sees in their browser. Once loaded, JavaScript can interface with the DOM and make updates to change what the user sees. The DOM has a tree-like structure, allowing developers to use JavaScript code to search it or modify specific elements. Let's take a look at a practical example:

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello World!</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1> Hello Moon! </h1>

<p> The earth says hello! </p>

</body>

</html>If you want to play with the DOM, you can copy the code above to a file called index.html and open it using your browser. The document element is always the head of the tree. The subtree html is where all the HTML code of the loaded webpage would live, which is divided into head and body. You can view the DOM using your web browser's built-in Developer's Tools by right-clicking the page and selecting the Inspect option.

Using the developer tools, we can also interface with the JavaScript console and use this to modify the DOM. For example, we could create a new element in the DOM using the following instructions:

Click the Console button

Create a new paragraph:

const paragraph = document.createElement("p");Create a new text node:

const data = document.createTextNode("Our new text");Add the text to our new paragraph:

paragraph.appendChild(data);Find the existing paragraph and append the new paragraph:

document.getElementsByTagName("p")[0].appendChild(paragraph);Your new text should be loaded, as shown below.

This is also where the true power of DOM-based attacks lies. If we can inject into the DOM, we can alter what the user sees or even potentially take actions as the user, effectively impersonating them! This became a significantly larger problem with modern web application frameworks or so-called single-page web applications where control over the DOM does not just mean control over a single webpage but persistence across the entire web application.

Modern Frontend Frameworks

Back in the Old Days

The last bit of theory before we dive into the world of DOM-based attacks is modern frontend frameworks. Conventional web applications were built where the response to each web request would refresh the entire DOM, as shown in the example request below:

As shown in the example, each time a user navigated to a different section in the web application, the response provided to the request made would provide completely new HTML code, and the DOM would be rebuilt from scratch. However, this was quite cumbersome and decreased the responsiveness of web applications.

The Rise of Modern Times

With the rise of modern frontend frameworks, birth was given to a new web application model called the single page application (SPA). SPAs are loaded only once when the user visits the website for the first time, and all code is loaded in the DOM. Leveraging JavaScript, instead of reloading the DOM with each new request made, the DOM is automatically updated, as shown below:

Instead of reloading the DOM with each request, the responses only contain the data required to update the DOM. This drastically reduces the amount of overhead with each request and while the initial load of the web application may take longer, it is much more responsive when being used.

Modern frontend frameworks such as Angular, React, and Vue allow developers to create these SPAs. Instead of the web server being responsible for the DOM as well, the SPA is loaded once and then interfaces with the web server through API requests. While this increases the responsiveness of the web application, it can lead to interesting misconfigurations and vulnerabilities. The two most common are discussed below.

Confusing of the Security Boundary

The first common mistake is confusing where the security boundary sits. There is a common saying in application security that states: "Client-side controls are only for the user experience; all security controls must be implemented server-side". This is important because a threat actor can control everything in the browser and, thus, can be bypassed.

Not understanding this principle most commonly leads to authorisation bypasses. An example of this is when the developers disabled the "edit" button in JavaScript. However, since you can alter the DOM in your browser, you can re-enable the button and make the request, thus leading to an authorisation bypass. While it creates a better user experience to have the button disabled, a server-side security check is still needed to ensure that the user making the request has the relevant permissions to perform the edit action.

Insufficient User Input Validation

The second common mistake is not sufficiently validating user input. This often happens when the frontend and backend development teams do not communicate who is taking responsibility for certain security controls. The frontend team will often implement filters to sanitise or validate user input before it is sent in a request to the web server. However, as mentioned before, threat actors can bypass frontend controls. Therefore, the frontend team should ensure that the backend team performs the same input validation and sanitisation when data is sent in requests. However, because the backend team usually does not know exactly how the frontend works, they are more likely to send raw, unsanitised and unfiltered data to the frontend in responses, expecting the frontend team to perform the sanitisation on the data before displaying it in the application.

This can often lead to no team taking responsibility for input validation. As each team expects the other team to deal with security, it can often create security gaps, allowing for attacks such as Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) or Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF). This problem is compounded in the modern age, where most applications no longer work in isolation but are heavily integrated with other applications and systems. While unsanitised data injected into Application A may be harmless to Application A, the developers of Application B may incorrectly assume that this data has been sanitised, leading to a vulnerability in Application B through data sent via Application A.

DOM-Based Attacks

With our background information complete, we can finally look at DOM-Based Attacks. In the previous task, it was mentioned that client-side security controls are only for the user experience. However, with the rise of modern frontend framework applications, this rule no longer holds true. Ignoring client-side security controls is exactly what leads to DOM-based attacks.

The Blind Server-Side

While there are many different DOM-based attacks, all of them can be summarised by insufficiently validating and sanitising user input before using it in JavaScript, which will alter the DOM. In modern web applications, developers will implement functions that alter the DOM without making any new requests to the web server or API. For example:

A user clicks on a tab in the navigation pane. As the data on this tab has already been loaded through API requests, the user is navigated to the new tab by altering the DOM to set which tab is visible.

A user filters the results shown in the table. As all results have already been loaded, through JavaScript the existing dataset is reduced and reloaded into the DOM to be displayed to the user.

In these examples and many other actions, no requests are made to the API, as there is no need to refresh the data being shown to the user. However, this leads to an interesting issue. What would protect us now if all of our security controls for data validation and sanitisation were implemented server-side? Therefore, with the rise of modern web applications, client-side security controls have become a lot more important.

The Source and the Sink

As mentioned before, all DOM-based attacks start with untrusted user input making its way to JavaScript that modifies the DOM. To simplify the detection of these issues, we refer to them as sources and sinks. A source is the location where untrusted data is provided by the user to a JavaScript function, and the sink is the location where the data is used in JavaScript to update the DOM. If there is no sanitisation or validation performed on the data between the source and sink, it can lead to a DOM-based attack. Let's reuse the two examples above to define the sources and sinks:

Example

Source

Sink

User clicking a tab on the navigation pane

When the user clicks the new tab, a developer may update the URL with a #tabname2 to indicate the tab that the user currently has active.

A JavaScript function executes on the event that the URL has been updated, recovers the updated tab information, and displays the correct tab.

User filtering the results of a table

The input provided in a textbox by the user is used to filter the results.

A JavaScript function executes on the event that the information within the textbox updates and uses the information provided in the textbox to filter the dataset.

The first example is quite interesting. Even though the initial user input was a mouse click, this was translated by the developers in an update to the URL. Using the # operator in the URL is common practice and is referred to as a fragment. Have you ever read a blog post, decided to send the URL to a friend, and when they opened the link, it opened at exactly the point you were reading? This occurs because JavaScript code updates the # portion of the URL as you are reading the article to indicate the heading closest to where you are in the article. When you send the URL, this information is also sent, and once the blog post is loaded, JavaScript recovers this information and automatically scrolls the page to your location. In our example, if you were to send the link to someone, once they opened it, they would view the same tab as you did when creating the link. While this is great for the user experience, it could lead to DOM-based attacks without proper validation of the data injected into the URL. With this in mind, let's look at a DOM-based attack example.

DOM-based Open Redirection

Let's say that the frontend developers are using information from the # value to determine the location of navigation for the web application. This can lead to a DOM-based open redirect. Let's take a look at an example of this in JavaScript code:

goto = location.hash.slice(1) if (goto.startsWith('https:')) { location = goto; }

The source in this example is the location.hash.slice(1) parameter which will take the first # element in the URL. Without sanitisation, this value is directly set in the location of the DOM, which is the sink. We can construct the following URL to exploit the issue:

https://realwebsite.com/#https://attacker.com

Once the DOM loads, the JavaScript will recover the # value of https://attacker.com and perform a redirect to our malicious website. This is quite a tame example. While there are other examples as well, the one we care about is DOM-based XSS.

There are other types of DOM-based attacks, but the principle for all of these remain the same where user input is used directly in a JavaScript element without sanitisation or validation, allow threat actors to control a part of the DOM.

DOM-Based XSS

DOM-based XSS is a subsection of DOM-based attacks. However, it is the most potent form of DOM-based attack, as it allows you to inject JavaScript code and take full control of the browser. As with all DOM-based attacks, we need a source and a sink to perform the attack.

The most common source for DOM-based XSS is the URL and, more specifically, URL fragments, which are accessed through the window.location source. This is because we have the ability to craft a link with malicious fragments to send to users. In most cases, fragments are not interpreted by the web server but reflected in the response, leading to DOM-based XSS. However, it should be noted that most modern browsers will perform URL encoding on the data, which can prevent the attack. This has led to a decrease in the prevalence of these types of attacks through the URL as source. Let's look at an example where a fragment in the URL can be used as a source.

DOM-based XSS via jQuery

Continuing with our web page location example, let's take a look at the following jQuery example to navigate the page to the last viewed location:

Since the hash value is a source that we have access to, we can inject an XSS payload into jQuery's $() selector sink. For example, if we were able to set the URL as follows:

https://realwebsite.com#<img src=1 onerror=alert(1)></img>

However, this would only allow us to XSS ourselves. To perform XSS on other users, we need to find a way to trigger the hashchange function automatically. The simplest option would be to leverage an iFrame to deliver our payload:

<iframe src="https://realwebsite.com#" onload="this.src+='<img src=1 onerror=alert(1)>'

Once the website is loaded, the src value is updated to now include our XSS payload, triggering the hashchange function and, thus, our XSS payload.

This is one example of how XSS can be performed. However, several other sinks could be used. This includes normal JavaScript sinks and framework-specific ones such as those for jQuery and Angular. For a complete list of the available sinks, you can visit this page. As shown above, the tricky part lies in the weaponisation of DOM-based XSS. Without proper weaponisation, we are simply performing XSS on ourselves, which has no value. This is a key issue with DOM-based XSS. Luckily, weaponising can be performed through the conventional XSS channels!

DOM-Based XSS vs Conventional XSS

When you are looking for XSS, while it may seem to be normal stored or reflected XSS. In some cases, it may actually be stored or reflected DOM-based XSS. The key difference is where the sink resides. If the untrusted user data is already injected into the sink server side and the response contains the payload, then it is conventional XSS. However, if the DOM is fully loaded and then receives untrusted user data that is loaded in through JavaScript, it is DOM-based. While there may not be a difference in the exploitation of XSS, there is a difference in how the XSS should be remediated. In the former, server-side HTML entity encoding should be used. However, in the latter, a deeper investigation into the exact JavaScript function that loads the data is required. In most cases, a different function should be used.

XSS Weaponisation

To weaponise DOM-based XSS, we need to rely on the two conventional delivery methods of XSS payloads, namely storage and reflection. This is why DOM-based XSS, and other DOM-based attacks for that matter, are so hard to exploit. Without a proper delivery method, you are performing the attack on yourself and not a target.

To counter this, we either need the web server to store our payload for later delivery or to deliver the payload through reflection. At this point, our DOM-based XSS becomes a Stored or Reflected XSS attack. This room expects you already to understand the fundamentals of XSS and its different forms. If you need a refresher, you can take a look at this room.

As mentioned in the previous task, reflected XSS, especially when the source is the URL, can become tricky as modern browsers perform URL encoding. This generally leaves us with stored XSS as a delivery mechanism. However, this also opens up several additional sources for us. If we perform XSS through stored user data, we need to find a sink where this data is added without sanitisation or validation.

General Weaponisation Guidelines

Before we take a look at a case study, it is worth first talking about general XSS weaponisation. Oftentimes, you will find that it is easy to get the coveted alert('XSS') payload to work. However, this is usually where the fun ends, and if we are being honest with ourselves, we haven't actually shown impact.

The next crutch that is often used is to attempt to steal the user's cookie. However, this quickly becomes a problem when cookie security is enforced by using the HTTPOnly flag, disallowing JavaScript from recovering the cookie value. We need to dive deeper to weaponise the XSS vulnerability to achieve a valid exploit and show the true impact of what was found.

The following is a great article that talks about XSS weaponisation. To fully weaponise XSS, we first need to realise the power of what we have. At the point where we can fully execute XSS and load a staged payload, we can control the user's browser. This means we can interface with the web application as the user would. We don't need to pop an alert or steal the user's cookie. We can instruct the browser to request on behalf of the user. This is what makes XSS so powerful. Even if you find XSS on a page where there isn't really anything sensitive, you can instruct the browser to recover information from other, more sensitive pages or to perform state-changing actions on behalf of the user. All we need to do is understand the application's functionality and tailor our XSS payload to leverage and use this functionality to our advantage. Let's take a look at a case study.

DOM-Based XSS Case Study

In 2010, it was discovered that Twitter (now X) had a DOM-based XSS vulnerability. In an update to their JavaScript, Twitter introduced the following function:

Effectively, the function searched for #! in the URL and assigned the content to the window.location object, creating both a source and a sink without proper data validation and sanitisation. As such, an attacker could get the coveted pop-up simply using this payload:

http://twitter.com/#!javascript:alert(document.domain);

As mentioned before, this wouldn't really do anything. However, the issue was weaponised by threat actors. The vulnerability was weaponised using the onmouseover JavaScript function to create a worm that would:

Retweet itself to further spread to new users

Redirect users to other websites, in some cases containing further malicious payloads.

Display pop-ups and other intrusive behaviours that could potentially phish for personal information.

In the end, the weaponised exploit affected thousands of users. It is worth remembering that this was in 2010. If such a bug were found today, the impact would be even larger.

DOM-Based Attack Challenge

Now that you understand DOM-based attacks and, more specifically, DOM-based XSS, it is time to put your knowledge to the test. Start the attached machine. You may access the VM using the AttackBox or your VPN connection. The VM takes around 3-4 minutes to start. Once ready, use the following code to add an entry to your hosts file:

sudo echo 10.10.161.155 lists.tryhackme.loc >> /etc/hosts

You can then navigate to http://lists.tryhackme.loc:5173/ . Here, you will find a simple birthday list application that is vulnerable to a stored DOM-based XSS attack. While you can add and update birthdays, you cannot delete them. You aim to weaponise the XSS vulnerability to recover the information required to delete birthdays. Once you delete all of them, you will receive your flag!

Enumeration of a Modern Frontend Application

In order to do this challenge and answer the questions, you will need to analyse the Vue application. Navigating to the application you will see the following:

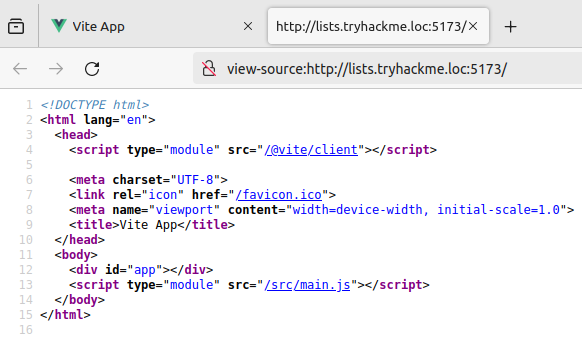

If you simply use View Page Source, this doesn't really help you a lot:

However, the browser will actually rebuild the Vue application for us in the debugger. You can access the debugger by Right-Clicking, selecting Inspect, and then clicking the Debugger tab. You will see the following:

Using this, you can navigate to src -> components, which will show you the rebuilt (referred to as mapped) Vue files, as shown below:

You will have to use this feature to solve the challenge and answer the questions below!

Hint: You need to trick another application user into giving you sensitive information. However, if you alert this user, they will become suspicious and simply stop using the application. You can console them by either logging while you perform your tests or restarting the entire machine. Furthermore, if you are able to get an interaction from the user but it isn't exactly what you were hoping for, perhaps the answer is to monitor the user closer and for longer!

v-html can be used for HTML Injection

Link: https://vuejs.org/guide/best-practices/security

If I try to delete the secret I see the following in the tabs 'Console' and 'Network'.

Kali

Payload

With our payload we're able to get the cookie for other users.

Updated the secret in the cookie.

After updating the secret I was able to delete all the birthdays.

Last updated